| Hana Kofler

Hadera, Khotin, Hadera: 1944-1948

Moshe Givati was born in Hadera in 1934. He was named Moshe Hacohen Wexler after his late father, who died at 21. Givati’s parents, Yehudit and Moshe, immigrated to Palestine from the Bessarabian town of Khotin in 1933, having married at a young age. The bride’s parents consented to the couple’s immigration to Palestine on condition that they first marry. The two joined a group of young pioneers, Hachsharat Masada, which was affiliated with the Gordonia movement. Upon their arrival in Palestine, Yehudit and Moshe settled in Hadera, and were sent to work in road paving. In those years the country experienced a boom in immigration, construction and development, which was dubbed the “prosperity” period, due to the steady rise in the standard of living and the rapid urban growth. But the prosperity period was relatively short, ending late in 1935, following the Italian-Ethiopian War which threatened Britain’s status in Palestine.

Givati’s father, Moshe Wexler

Hacohen Ben Elazar, Hadera, 1933

Givati’s mother, Yehudit, never talked with her son about his father’s death, in fact avoiding any mention of her late husband who passed away shortly after their arrival in Palestine, some three months before his son’s birth. She broke off all contact with the late father’s family as it had objected to the marriage from the outset. At 17, as reinforcement in Kibbutz Sha’ar Ha’amakim, Givati managed to locate his father’s burial place, at the Khayyat Beach Cemetery, Haifa. Only recently did he find out that his father had been stricken with dysentery, rushed to the government hospital in Bat Galim, where he died, and was thus buried in Haifa rather than Hadera, his place of residence. The gravestone which Givati found, bore the following succinct epitaph: Moshe Wexler, son of Elazar, died at the age of 21 (the name “Hacohen” was omitted from his full name for some reason). To date, these facts are all Givati knows about his father. Regarding his early childhood years, he has managed to gather more orderly information from hearsay, and therefrom compose the first chapter in his personal chronicles.

Moshe (Givati) and his mother, Yehudit,

Khotin, Bessarabia, 1939

My mother worked with the group that built the Sargel Road to Afula. After she gave birth, she couldn’t keep me with the labor force; the conditions there were unfit for child rearing. Thus, after much wandering, she brought me to my grandmother in Khotin, and went back to Palestine on her own. I was two years old. In 1939, on the eve of World War II, my mother went with a group of friends to visit their families in Khotin and brought me back here. I was thus saved from the horrors of World War II. We embarked on the last ship that set sail from the port of Constanta in Romania. I was nearly five. I remember arriving at the Haifa Port and the sky was full of giant helium balloons attached to wires as camouflage against the Italian air raids mainly directed at the port and refineries in the Haifa Bay, which were protected by means of thick smoke. We went to Hadera. My mother worked as a night guard in the Working Women’s Farm. She had an apartment there. I lived with her and went to the Working Mothers’ Organization kindergarten. I couldn’t speak a word of Hebrew. I spoke Yiddish and Russian. I quickly relearned Hebrew, but apparently I was a dyslectic child and had great difficulty reading. My mother was a simple laborer and there was no one to help me.

Givati’s grandparents (on his mother’s side),

Henia and Tuvia Leib Shenker, Hadera, 1950s

In 1944, when I was about 10, my mother remarried and we moved to live with a group of laborers in an orchard in the Tel Mond area. The bachelors in the group lived in the packing house, and the families were given shacks. When my sister Zfira was born, the place became crowded, and I moved to live on my own in a tent. I went to the Tel Mond Regional School every day by donkey. I used to tie the donkey and at the end of the school day ride back to the orchard. Sometimes the donkey would run away, or simply stop midway and refuse to budge, and therefore I missed school quite often, but no one cared. Aaron Priver was our art teacher. I remember that he told us to copy a horse which he drew with great accuracy on the blackboard. He used to walk about the room with a ruler in hand and slap pupils’ hands. He wasn’t all that popular. When the War of Independence broke out, it became dangerous to live in the orchard, and we returned to Hadera. My mother found an apartment in the Brandes neighborhood. I resumed studying at Beit Hinuch Workers’ Children School. The school bordered on the Yemenite Neighborhood which was the stronghold of local Irgun (IZL) forces. The Yemenites lived separately, outside the camp, and had no contact with the laborers, except for Zachariah’s falafel cart with the intoxicating aromas that emanated from it. We used to gather by the cart which was located near the bakery whenever we had a Mill or two in our pocket. For some reason, the Yemenites did not belong to the Labor stream, even though the men used to go out every morning with hoes to work in the orchards, and the women – to clean houses. They were simply from ‘there’ and lived in absolute autonomy. The children studied in Tachkemoni which was, of course, an orthodox school. The observant Ashkenazim had a separate school as well. In Beit Hinuch, which was considered a liberal institution, they never checked why a child didn’t study, and were never strict about our level of education. It thus happened that until quite late I couldn’t read at all. I scribbled and drew a lot in my notebooks, and then, at some point, I was kicked out of school (All the quotations are from the author’s conversations with Givati, unless indicated otherwise).

Kibbutz Sha’ar Ha’amakim: 1948-1958

At 14 Moshe Givati went out to work. Initially he worked in a small factory for towels and tablecloths, wherefrom he shifted to working on an old kerosene-operated tractor, but was exploited by his employer who paid him scanty wages. The War of Independence was at its height, and all the men were drafted, thus the need arose for working hands. Givati soon received an offer to work on a large, modern tractor, and join workers laying the new railway tracks connecting Hadera and Tel Aviv. He made 6 Lira per shift in this job, a considerable sum in those days, from which he gave money to his parents and also managed to purchase a Matchless motorcycle. Later on, when his stepfather purchased a tractor and tools, the skilled Givati was entrusted with their operation. He did not get along with his stepfather, however, and therefore gathered all the equipment in the yard and left the house. He went to the Hashomer Hatzair headquarters on Allenby Street, Tel Aviv, and asked to join a kibbutz. As in the case of many other children whose parents were immersed in hard work and busy with the trials and tribulations of life, for Givati too, the youth movement became a refuge, even a life saver. The youth movement in those days certainly left its imprint on the youth, and its influence on the course of their lives was greater than that of their family home or the education they received in school. As a youth who failed in school and found no open ear at home, the movement became the center of Givati’s life. At Hashomer Hatzair he met middle class children who attended the general school in Hadera. Hashomer Hatzair, which belonged to the United Workers’ Party (Mapam) had at the time the reputation of a more respectable movement than Hanoar Haoved (Working Youth), and thus it was more popular among youngsters and parents, even those who were ideologically affiliated with other parties, like Givati’s mother who was a devout adherent of Israel Workers’ Party (Mapai).

The father’s grave, Khayyat

Beach Cemetery, Haifa

In the Tel Aviv offices I was told that a group was being organized in those days for agricultural training in Kibbutz Sa’ar in the Western Galilee. I was given a shopping list; I packed all the necessary equipment and hit the road. After a short stay in Sa’ar the truck took us to Kibbutz Shamir. At that time I painted quite a lot, but kept none of it. There was someone in Kibbutz Shamir who painted a little, and he was also a little bit of a musician. Then Moshe Kagan, who emigrated from Russia, arrived at the kibbutz, and on special occasions such as May Day he used to decorate the dining room with portraits of Lenin and Stalin. I just painted on stencil paper and anything at hand. Every now and then I would prepare some decorations for the youth club house. We worked half a day and studied. After two years Hashomer Hatzair secretariat decided that we should move to Sha’ar Ha’amakim. We joined the youth group that was educated in the kibbutz, and were defined as a complementary group to the class of three eldest girls who were the same age as us, and two of the “Teheran children” – one of them, Alex Levy, was a gifted painter who later died in tragic circumstances, and the other – Reuven Yaron, a wonderful musician who fell in the Sinai Campaign in Dahab. We stayed there until we were drafted by the Nahal Command.

Moshe Givati, Yael, Vered, Ben-Zion,

and Nir, Kibbutz Sha’ar Ha’amakim, 1960

Together with his peers Givati joined the Nahal. During his military service, due to an inexplicable urge, he says, he often drew on a notepad that he always kept with him. Despite his strong tendency to paint in color, the conditions in the field and the transience that characterized the military routine prevented him from painting more than these drawings to which he devoted every spare moment. From this early period in his artistic career, and even from the first years after he was discharged from the army, no documentation has survived. His earliest works located with friends, collectors and family members, all date back to the early 1960s, and include mainly paintings in gouache on paper and watercolors.

In Kibbutz Sha’ar Ha’amakim he met Yael Givati, who was born on the kibbutz. He was twenty and she was nineteen when they married. In those days he was still known by the name Wexler, but after several years he adopted his wife’s last name. The marriage brought about a change in his life. He moved to live in a “family room,” and set up a painting corner on a chair, where he painted mainly in gouache. That same year a daughter, Vered, was born, and some eighteen months later – a son, Ben-Zion, and several years later – their third son, Nir.

When the painting corner in the family room became too small to contain his work materials, Givati took over one of the old shacks in the kibbutz and made a studio for himself. The kibbutz artist’s status in those days was indefinite, and members used to hold long discussions on the subject. Values such as the work ethic and one’s contribution to the community were a top priority for the Kibbutz Movement, and the artists who lived on kibbutzim were forced to fill work quotas equal to those of the other members, and engage in art in their spare time. In the course of time, usually after stormy discussions in members’ meetings, the kibbutzim started to make life slightly easier for artists, and allot time for their art. At first these were allotments of a few hours, but artists who established their status in the kibbutz, proved their talent and contributed to the community (by decorating the dining room on festivals and various occasions), were gradually given, in keeping with the criteria determined in the members’ meetings, a few days a week to practice their art. At some stage Givati enjoyed this privilege as well, but theretofore he worked as driver on a Mack truck, and spent most of his work time outside the kibbutz.

Tel Aviv – The Early Years: 1958-1963

I traveled throughout the country: Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, Eilat. I worked as a driver, and would often arrive in Tel Aviv. I stayed in the Geula Hotel on Geula Street, where all the Party’s “big shots” stayed. In Tel Aviv of those days there were plenty parking spaces for the Mack diesel. In my free time I strolled in the city and became acquainted with Chemerinsky Art Gallery and Katz Gallery. There was also Rosenfeld, but he mainly engaged in framing, and in the window of his workshop he used to exhibit paintings that came in to be framed. Only at a later stage, after selling many paintings, did he gather a collection and then transform the shop into a real gallery. I always used to pass by his window on Dizengoff Street. In 1959 I took my portfolio with me and entered Rosenfeld’s place. He opened the portfolio, liked what he saw, and immediately bought five works on paper. He paid me 250 Lira cash, and said that he would exhibit a painting of mine in the window the next week. This was the heart’s desire of many painters. For me it was a big thing. When I was visiting, he exhibited Mokady and Janco in his window. He sold my paintings. I kept in touch with him, and later he even made the contact between me and Haya Avni of Chemerinsky Art Gallery.

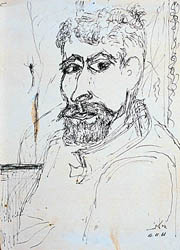

Self-Portrait, 1961, ink on paper,

25 x 25, private collection, Tel Aviv

Artistic activity in the Tel Aviv of those days was lively. The Helena Rubinstein Pavilion for Contemporary Art was opened in January 1959, and in April that year the ninth exhibition of the New Horizons artists was held there. Dizengoff House was still active, and presented the General Exhibition of Painters in Eretz-Israel. The Association of Painters and Sculptors staged the exhibition “Modern Art in Israel.” In 1960 Naftali Bezem, Shmuel Boneh, Michael Gross, Pinchas Shaar, Jacob Pines, and Aviva Uri were sent to represent Israel in the Venice Biennale. In March 1961 Samuel (Sam) Dubiner opened Galerie Israel on the corner of Frishman and Ben Yehuda Streets, which was managed by Barry Kernerman. The inaugural exhibition showed most of the New Horizons artists, among them Zaritsky. In April, an exhibition of twelve painters, including Argov, Wechsler, Okashi, Krize, Abramovic, Streichman, Stematsky, Giladi, and Mati Basis, opened. Danziger, Feigin, and Tumarkin exhibited sculptural works in that show. Zaritsky and Abramovic were no longer among the participants. At the end of that year, Yehiel Shemi, Yitzhak Danziger, and Shamai Haber represented Israel in an international sculpture exhibition at Musée Rodin, Paris. Exhibitions of young artists were held in the foyer of Eked Publishing House. In 1962 an international sculpture symposium was held in Mitzpeh Ramon, organized by Kosso Eloul, who was also one of the participants alongside Dov Feigin and Moshe Sternschuss, and eight foreign sculptors who were invited. Curator Haim Gamzu selected the artists for the Venice Biennale that year.

As aforesaid, Givati spent the period driving. Once in a while he went to Oranim Seminary to sketch nude figures after a live model, where he also studied with Marcel Janco. But he was much more fascinated by Tel Aviv and its galleries, and used his spare time to become better acquainted with the big city. In late 1961 he came across an advertisement published by the Tel Aviv Museum in Al Hamishmar (to which he was subscribed as a kibbutz member); Haim Gamzu was inviting young artists from all over the country to submit works for an exhibition in memory of Eugen Kolb, the late director of the Tel Aviv Museum. Givati submitted three framed paintings, and all three were accepted for the exhibition which was held at Dizengoff House. These paintings depicted semi-abstract landscapes executed in mixed media on paper. Raffi Lavie, Joseph Gattegno, Shlomo Cassos, and other young artists participated in that exhibition as well. Gamzu was impressed by Givati’s works and wanted to meet him personally. This was the first exhibition in which Givati participated, and thereafter Gamzu included him in all the Autumn Exhibitions he curated at the Helena Rubinstein Pavilion for Contemporary Art. Later he would sign him on a contract for a solo exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum.

In one of Givati’s visits to Rosenfeld he met Pinchas Abramovic who invited Givati to visit him at home in Ramat Aviv. A friendship developed between the two, and Givati became a frequent visitor to Pinchas and Emma Abramovic’s home. They gave him a spare key and invited him to stay there whenever he wanted. In the meetings arranged by Emma in their home, Givati became acquainted with the New Horizons’ artists, and Abramovic opened a new world to him and enlightened him with regard to the dominant artistic trends prevalent in the city. Givati was mainly influenced by the coloration of Zaritsky, by Abramovic himself, and by Streichman; he assimilated the influence of Lyrical Abstract into his unique painterly structures which differed from his sources of inspiration.

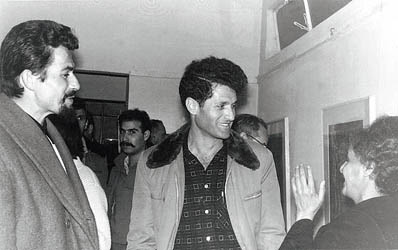

Bracha Zefira, Nathan Yonathan, and Moshe Givati in the opening of

Givati’s exhibition at Chemerinsky Art Gallery, Tel Aviv, 1962

As aforesaid, it was Eliezer Rosenfeld who recommended Givati to Haya Avni, wife of painter Aharon Avni, who in 1954 founded the Avni Art Institute with the help of the Histadrut, the General Federation of Labor in Israel. Most of the teachers at Avni were members of New Horizons. Chemerinsky Art Gallery, which was managed by Haya Avni, was located on Gordon Street. Avni’s studio was in the basement of that building (The gallery itself was named after the late Habima actor – Baruch Chemerinsky, as per the requirement of his widow who owned the property). Haya Avni examined Givati’s portfolio and set a date for an exhibition: February 1962. Then the issue of his name came up, since he was still called Wexler at the time. In those days he didn’t sign his paintings until he sold them. Of that period several works remain bearing the signature with his original name, “Wexler Hacohen”. Per Haya Avni’s demand, he was asked to sign the paintings to be exhibited in the gallery before the exhibition, but she was not happy with the name Wexler, and asked him to take a Hebrew name. She said there were too many painters named Wexler/Wechsler (Jacob Wechsler, and even another Moshe Wexler), and was afraid that the audience would mistake him for the seasoned Moshe Wexler, even though each of them spelled his name differently in Hebrew. Moshe Hacohen Wexler forthwith adopted his wife’s maiden name (which had been Hebraized by her late father, before he was killed stepping on a mine in the Kibbutz fields during the 1936 Riots), and legally became Moshe Givati. He continued to avoid signing his paintings later on as well, waiting until they were to be exhibited or sold. Rosenfeld framed the paintings, and Givati was entrusted with the task of mounting the exhibition. Years later he recounted how he stood helpless facing the gallery walls, clueless as to how to hang a professional exhibition. Moshe Prupes, who accidentally walked in, came to his rescue. He sent him to the movies, to see Godard’s La Chinoise at the Paris Cinema. Prupes reduced the number of paintings for display, skillfully placed the works one next to the other, and when Givati came back from the film, the exhibition was already mounted.

Joav BarEl, later to become Givati’s best friend, had already replaced Dr. Gamzu as art critic of Haaretz at the time. In his column “Exhibitions in Tel Aviv” he published the first review about Givati’s first solo exhibition:

The first solo exhibition of Moshe Givati, member of Sha’ar Ha’amakim, is purely comprised of gouache. Givati’s work is not yet consolidated, and the exhibition spans three periods of the painter’s quest for self-acquaintance. Givati tends to build up atmosphere by means of color, but the color strokes still surrender great hesitation which is manifested in the amassment of color upon color, resulting in their mutual blurring. Givati attempts to reinforce the structure by employing lines that do not stem from the color application and appear ‘glued.’ Having studied at the Avni Institute of Painting and Sculpture, Givati’s painting also evinces the influences of his teachers; in Painting in Ocher and other paintings, one may discern mainly Krize’s influence. It seems that Givati still has to digest these influences fully and take more care with the interrelations between the line, the stain, and the geometric structure. He must beware mainly of the easy solution of using grays and neutral colors in a color clash (Haaretz, 9 March 1962 [Hebrew]).

Art critic P. Friedberg also referred to the exhibition in an article published that day in Al Hamishmar:

Moshe Givati, native born Israeli and member of Kibbutz Sha’ar Ha’amakim, studied with Marcel Janco and at the Avni Art Institute, but acquired most of his painterly education by observing young art in exhibitions throughout the country. A blessed influence on him was that of the “beautiful stain” painting. Many of his paintings are composed of tiny rectangles of color linked together with fine pen drawing, a la Mieslewitz. The subject matters in these paintings are ships mooring at port, buildings, etc.

Other paintings consist of larger color surfaces – and in these too, the drawing is significant as a linking and defining element, whereby a yellow stain, for example, transforms into the wall of a building with an arched window, or a rock.

Moshe Givati, as aforesaid, is still at the very beginning of his career, and it is therefore hard to determine the true quality of his paintings. He covets all, and in his efforts to master motif and atmosphere, harmonious colors, a rhythmical composition and the material, the picture itself is lost. His paintings also display a certain measure of slovenliness which attests to a quick execution devoid of sufficient knowledge. Nevertheless, the exhibition reveals signs of talent. Lilith is a perfect, beautiful painting. The entire paper is covered with small stains of dark, crude color reminiscent of a tree trunk. The bird merges with the background, and yet is slightly accentuated. This is partly achieved by drawing in thin pen lines which do not contradict the general painterly nature. Everything is seemingly warm brown, but in the midst of this color – blue, orange and frost-white draw our attention.

Let us wish that at a later date the artist will be able to exhibit many more paintings of this quality (Al Hamishmar, 9 March 1962 [Hebrew]).

Moshe Givati, Tel Aviv, 1962,

Photograph: Ephraim Erde

All the paintings featured in that exhibition were sold. Following the exhibition at Chemerinsky, Givati was exposed to the Tel Aviv art scene and began to comprehend its power structure and the parties involved. New Horizons was still grouped officially at the time, but was already at the end of its activity as an organized group. Its tenth and last exhibition was held in 1963 at Mishkan Le’Omanut, Museum of Art, Ein Harod. In addition to Arie Aroch, the participants included Tumarkin, Raffi Lavie, Ury Lifshitz, Moshe Kupferman, Arie Azéne, and other young artists who were not members of New Horizons.

That same year, the 8th Congress of ICA (the International Association of Art Critics) was held in Israel, with the participation of some of the leading art critics and historians of the time. The Israeli artists received extensive exposure in the myriad exhibitions held on that occasion: The Tel Aviv Museum staged an exhibition of select Israeli art organized by the Department of Painting and Sculpture of the Public Council for Culture and Art, featuring forty artists. Bezalel presented a solo exhibition of Mordecai Ardon, which later traveled to all the prominent museums in Israel. Special exhibits for the congress participants were held in the Museum of Modern Art, Haifa, in Ein Hod, Safed, and the Artists’ Pavilion, Jerusalem. In the wake of these events, Israeli artists (most of them members of New Horizons) were invited to exhibit at Galerie Charpentier, Paris, which focused mainly on abstract art, and a year later – at the Guggenheim Museum, New York. Givati, still a member of Kibbutz Sha’ar Ha’amakim, participated that same year in the exhibition of Hakibbutz Ha’artzi Artists at Beit Hasofer, Tel Aviv. Joav BarEl, in his review in Haaretz, warmly recommended the exhibition, and commended Givati, saying that this multi-participant exhibition was equal in quality to other general exhibitions, and even stood out in comparison to other exhibitions of its kind. In the very same review, however, BarEl also chose to deride the

lip service and bombastic phrases opening the catalogue, whereby the kibbutz artist is guided by ‘an inner need to create art, and thereby express his belief in life, man, and the kibbutz.’ The real need guiding the kibbutz artist is likely the very same need that guides artists anywhere, without any added collective dimension, and it is all for the better. The enhanced artistic quality is not the result of a heightened awareness in communal social life, but rather due to a developing artistic consciousness and a growing sensitivity to the needs of form and color, which are the means of expression of any artist (Haaretz, 21 March 1963 [Hebrew]).

BarEl’s critique of the cliché of the pompous social ideology was not foreign to Givati, whose affinity with the kibbutz, its members and values, gradually diminished, despite his entitlement to one day for art per week – a privilege that was not granted to every kibbutz artist. In the meantime, his driver’s license had been revoked for a year, and he stopped driving the truck and worked in assorted jobs. They didn’t know what to do with him on the kibbutz, he says. On his free day intended for painting, he used to go to Acre.

There were two small taverns (Small eastern taverns where one drinks alcohol, smokes a hookah and plays backgammon). there. The fishermen used to bring their catch early in the morning. They would fry the fish, make hummus, and drink coffee. I met a few Arab fishermen there and they invited me to go fishing with them. Before going out to sea, after they completed all the preparations, I saw them rolling what looked like a giant cigar. They asked me if I wanted to try. It was top quality Lebanese hashish. After this first time they dragged me semiconscious to their home. I slept there until the afternoon. It gave me a jolt, I felt good. I kept in touch with them, and my friend, the fisherman, used to visit me on the kibbutz every now and then and bring hashish.

Within a short time Givati’s paintings underwent a radical transformation. The dramatic metamorphosis that occurred from the time he started depicting the Acre landscapes and fishermen to his quasi-Cubist monochromatic abstracts can only be explained as enlightenment due to a sudden development, or as a result of an accelerated process of learning that magically influenced his consciousness, stemming from constant observation of changes and transformations in the art world. These were always supplemented by the human figure, without which Givati could never manage, and now found its way back into his canvases, each set of figures and the narrative leading thereto.

|