| Hana Kofler

Europe – First Journey: 1963-1964

As aforesaid, Givati used to spend his allotted painting day outside the kibbutz. He often hung out in Tel Aviv, catching up on the goings-on in the local art scene and overseas. Finally he decided to go to Europe, mainly Paris, which was the longed for destination of Israeli artists in those days, although it had already lost its hegemony as “the capital of international art” to New York. Like the seasoned artists for whom the gates of Europe opened only in the wake of World War II, Givati yearned to visit the origins of painting, the museums and cathedrals, and see, first hand, the originals he theretofore knew only from reproductions. He asked the kibbutz for leave, was granted a month, and embarked on the S/S Moledet headed to Italy. During the voyage he painted ceaselessly on variously sized papers. One of the passengers noticed him painting on deck, sent him drinks at her expense, and purchased everything Givati created on board. Thus, Givati disembarked in Naples with a substantial sum of money. In Naples he met two priests who sat next to him in a pizzeria. They invited him for wine, and when they found out he was headed for Rome, they offered to drive him there. On the freeway to Rome they drove at a dizzying speed; on the way they stopped at a gas station and asked him to pay for a full tank. In Rome they dropped him off by a hotel adjacent to the central train station (during his entire trip in Europe Givati stayed close to train stations, fearing he would get lost). On the first morning of his visit to Rome, he went straight to the American Express office and purchased a combined European train and ferry pass. He took a train to Venice, where he stayed an enjoyable fortnight. From there he continued according to plan to Padua to view Giotto’s famous piece at the Arena Chapel: the fresco cycle he created circa 1305-1306, depicting scenes from the life of the Virgin and the Passion of Christ, works about which Matisse is known to have said that one does not have to be familiar with the stories of the New Testament in order to fathom their meaning, for their truth is inherent in them. Givati arrived there only to discover that the chapel’s frescoes were undergoing restoration, and the place was closed to the public. He checked into a small hotel in the city, and continually visited the chapel, insisting to be let in. Eventually he was indeed allowed to enter and view the spectacular frescoes through the scaffolding.

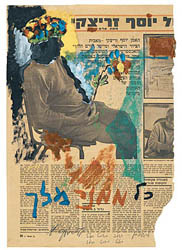

Untitled, 1971, mixed media on

newspaper, 42 x 29, collection of

Miriam and Herbert Goldman, Haifa

From Italy, Givati continued to Spain, first to Barcelona and then Madrid, where he stayed for a while in a small family pension next to the Prado Museum. He visited the Prado every day during his stay to observe, close up, the paintings he had known so well from reproductions, which far from reflected the power of the original. Zvi Mairovich had told him not to miss a certain painting that had captured his eye in any event: Velázquez’s Prince Baltasar Carlos on Horseback.

Three things overwhelmed me in that painting. I was fascinated by Velázquez’s repeated attempts to place the horse’s front leg accurately as he rises on his rear legs – he sought the critical point with graphite or pencil where the leg should be placed on the canvas. He left all his initial sketches on the canvas. It is rare for a painter to expose his searches for solutions and his deliberations in the work process to the viewer. Another thing was the horse’s eye: you could see that he had put white, ultramarine and black paint on the tip of his brush, gave one whirl, and that’s it, spontaneously. I was stunned. Also, the free azure brushstrokes of the sky were not as slicked up as I had thought, but rather liberated and tempestuous. It was an important lesson. I went to see this painting every day, and when the guards became suspicious that I was planning to steal it, they asked me why I didn’t go see Goya.

From Madrid, Givati took an organized tour to Toledo, and visited El Greco’s home. Standing there thrilled before the breathtaking vista and the paintings in their authentic birthplace, he missed the daily bus back to Madrid, and stayed with a local family. From Spain, he took the train to France. Initially he planned to stay in Paris for a while, but it wasn’t a week before he found himself on board a ferry that crossed the English Channel.

Painter Aaron Witkin had a brother in London who was a sculptor. One of his friends, who had a small hotel in London, waited for me in the port and hosted me in his hotel for about a week. In London I met Ezra Orion who told me about the St. Martin’s School of Art. I was especially impressed by Turner’s large-scale canvases, which were absolutely wonderful, and found London inundated with Francis Bacon’s works. Nouvelle figuration had already infiltrated the world of abstract, and later influenced my work as well, which in essence was not lyrical abstract at all, as it was often described.

Despite the turbulent ferry journey from France to England, Givati once again took the ferry to Amsterdam. It was late December. He rented a car and drove to the Kröller-Müller Museum to view Van Gogh’s originals. Here too he was in for a surprise due to the great gap between the flatness of the reproduction and the power of the original.

The Van Goghs in Kröller-Müller struck me because they were nothing like what you could see in the reproductions. Except for a single class with Prupes at Avni, and another class with Janco in Oranim, I never really studied painting, nor Art History. In fact, all that I know – brushwork, color strokes – I learned from observation of Zaritsky, Streichman, Stematsky, and some other members of New Horizons. And then I suddenly saw, in Van Gogh, what brushstrokes are. But this was not the end of the story with him. Within all the madness there I found great discipline and realized that nothing was placed on the canvas by accident.

Givati returned to Amsterdam in stormy weather, exhausted from his travels. The New Year drunkards celebrated in his hotel, and he decided to go back to Paris, thus foregoing the planned encounter with Rembrandt’s paintings.

This time Paris was less alienating. During his stay in the city, Givati met some Jewish artists who resided in the city and several Israeli artists who sojourned there. He rented a room in a hotel near Montparnasse, and to his surprise discovered that the shower was not included in the rent. He was also surprised by the number of exhibition salons in the city, which differed stylistically, thus enabling each artist to find a suitable platform for his work.

The Israeli artists were accustomed to struggles for hegemony. It was commonly believed that the “lyrical abstract”, which was predominant for many years due to Zaritsky’s unshakable authority, was the preferred style, and its status was considered higher than that of symbolical-national painting, for example (as represented by Mordecai Ardon). Artists of all other styles traditionally stood on one side of the divide, whereas the other side was occupied by the New Horizons artists (although it gradually became clear that even among them there was no stylistic homogeneity), and a harsh battle took place between these two groups.

During my stay in Paris, Jacques Greenberg and Uri Stettner exhibited in one of the painting salons in the city. I knew Jacques back in Tel Aviv, following his exhibition at Chemerinsky Art Gallery. He was an ardent communist. After the exhibition he left Israel and settled in Paris. At that time, he was a star in Paris and attracted great attention on account of two impressive canvases he painted.

One day, at Café Select, I met the younger brother of painter Arieli from New Horizons, who took me to see the Salon des Réalistes Nouvelles. They had a place of their own as well, and I realized that each one found his niche in Paris. But the ‘hottest’ name in the city was Marian, a real prince. I didn’t know him then, but I met him later, when I stayed in New York at the Chelsea Hotel. In Paris I already knew Hanna Ben Dov, whom I met when she came for a short visit in Israel during Pinchas Abramovic’s opening at the Holon Museum. She gave me her address and phone number. There I also met David Lan-Bar, who visited Israel at the time as well. I immediately went to see Hanna, and we became good friends. I met Lan-Bar between La Coupole and Select. He used to sit in the closed balcony of La Coupole, and when I joined him he would spout his bitterness. In Paris I also met Yehuda Neiman, Meir’ke Lazar, and other Israelis who hung out in the City of Lights, and there were many of them. I once saw Menash’ke Kadishman there; he entered La Coupole wearing a sheepskin coat. I settled in Paris. Naturally I went to the Louvre, but the long queue in front of the Mona Lisa scared me off. I saw the Impressionists, I visited the galleries, especially the small ones that exhibited works on paper, prints and etchings, and stayed there for quite a long time. After five months or so, when money ran out, I returned to Israel and received a cold welcome in the kibbutz. I told them I was willing to work as much as necessary during the high cotton season, and went to my shack to paint. I ordered stretched canvases and paints in the Association, and worked intensely. I was removed from the kibbutz work roster, and practically did what I wanted.

Tazpit: 1964

The members of the Tazpit group, which assembled on an ideological basis, perceived themselves as the followers of New Horizons, which ceased to exist as a group. Toward their first exhibition, held in the spring of 1964, they composed a manifesto where they attempted to define a shared painterly language. In fact, it was the strongest and most refined expression of the need to exhibit an uncompromising, homogenous exhibition of the abstract trend, including breakthroughs in the field of sculpture, and first touches of Pop Art. The group numbered some thirty artists, among them “alumni” of New Horizons, such as Streichman (who gave the group its name), Abramovic, Luisada, Wechsler, Okashi, Yehiel Shemi, Danziger, and others. These were joined by some of the artists from the “Group of Ten,” among them Eliahu Gat and Ephraim Lifschitz. The seasoned artists invited young ones to the group, some of whom already had participated in the tenth and last exhibition of New Horizons at Mishkan Le’Omanut, Museum of Art, Ein Harod. Among the younger artists were Raffi Lavie, Moshe Kupferman, Ury Lifshitz, Ziva Lieblich, Aïka Brown, Tuvia Beeri, Aron Doktor, Aaron Witkin, Buky Schwartz, Mati Basis, Tumarkin (whose name appeared in the catalogue, but he withdrew his participation before the opening due to disagreement, and his works were not presented), and others.

At the time Givati was, as aforesaid, still a member of Kibbutz Sha’ar Ha’amakim, but he was already much more involved in the inner life of the Tel Aviv art scene. It was Abramovic who invited him to take part in the Tazpit exhibition, where he presented an abstract oil painting with a cubist structure, one of a series of paintings that dealt with composition of abstract forms with rhythmic color clusters, usually of the same color family, to create works at once intense and restrained, on medium-size canvases.

This was the artists’ grandest hour. They provoked a storm in their demand “to exhibit their works in the museum space, to elicit agitation, to bring about a change in artistic life in Tel Aviv, and awaken public opinion to the wrongs done to painters and sculptors.” (Yair Kotler, Haaretz, 20 March 1964 [Hebrew]). Streichman, Argov, and Shemi conducted negotiations with the Mayor of Tel Aviv, Mr. Mordechai Namir, and with Dr. Gamzu, the Museum Director, in the name of the angry artists. The Tel Aviv Museum was forced to postpone a French exhibition scheduled for that date to allow the Tazpit group to stage its show. The professed goal of the group members was to fight for the Helena Rubinstein Pavilion, which was considered the most prestigious exhibition venue. Thus, after an adamant struggle on the part of the artists “against whims of foreign exhibitions and public relations” and for local art, the exhibition was held at the Helena Rubinstein Pavilion from April 14 through May 5.

The art-loving audience responded keenly to the daring exhibition, and the press was agitated as well. Tumarkin’s work trousers and cast shoe, like Buky Schwartz’s totem poles and Aïka Brown’s dolls, were elements still foreign in the mid-1960s Israeli art scene. The art critics, however, were not particularly impressed by the phenomenon already prevalent in the international scene, which, as usual, arrived in Israel somewhat belatedly. Rachel Engel discussed this in her essay “The Angry Fail to Shock: Veterans and Youngsters in Tazpit.”

The Tazpit group with its 30 members is probably the most comprehensive group of painters and sculptors to emerge from among the practitioners of plastic art in Israel – outside the framework of the Association of Painters and Sculptors. Moreover, it also seems to be the most versatile in its make-up, as it comprises well-known seasoned artists, such as Streichman and Kahana, alongside young artists at the outset of their career, such as Moshe Givati and David Ben Shaul (Maariv, 24 April 1964 [Hebrew]).

After noting that it was indeed time that artists confronted artistic values, as New Horizons did at the time, Engel goes on to describe the exhibition itself:

When you stroll about the three floors of the Helena Rubinstein Pavilion today, you realize that, in fact, the time came long ago. If Aïka’s black ‘dolls’ whose heads peek at you from behind apertures in a fabric screen hardened and stretched over the ‘relief,’ Tumarkin’s corduroy trousers and cast left work shoe, Schwartz’s architectural sculptures reminiscent of either totem poles or road signs, Aaron Witkin’s harmonious geometrical wooden structures, or Aron Doktor’s cold, rigorous metal works – had been presented in such a consolidated and implicit spectacle in museums years ago, they would have probably elicited strong echoes. Today, however, you pass by them almost indifferently, for similar works have already been exhibited in various art centers throughout the world, at times more perfected in their design, at times more imaginative, and in any event – much earlier…

Art critic Miriam Tal closely examined the works of the painters and sculptors who presented at the exhibition. After reviewing the sculptural works of Ezra Orion, Aaron Witkin, Aron Doktor, Buky Schwartz, Lea Vogel, Ury Lifshitz, Itzhak Danziger, and Yehiel Shemi (as for Tumarkin, Tal noted him separately at the end of her review, deeming him an important, innovative artist and a key figure in the exhibition), she maintains:

In painting, there is a fundamental difference between painters who possess knowledge, experience, even virtuosity, yet remain essentially conformist, and those who have learned not only to speak the language of abstraction, but also to articulate meaningful, valuable statements. In Abramovic’s work one sees light surfaces, slight squares, elegant strips, green flowering; in Argov’s one finds semi-’formless’ compositions, somewhat reminiscent of Schneider; one canvas contains a snow-white surface; the colors are usually gray, green, white, and light yellowish-brown. Arieli fuses the forms with broad strips in a diagonal composition and matching colors; Mati Basis’s work displays an overly ‘trendy’ type of abstract painting, ostensibly bold, an abstract growth of sorts influenced by Streichman; a green-blue painting with forms in slight relief elicits interest. Avigdor Luisada (who was much more significant as a still-life painter) depicts mainly vertical, parallel, light forms against a dark background, or cold colored forms. In the work of Ephraim Lifschitz, who constructs his canvases diagonally, in vernal colors, admiration for Mark Tobey is evident.

Two painters, each in his own way, have found refuge in the world of paradox. Moshe Prupes, who was a highly skilled and utterly modern figurative painter, presents canvases that are entirely red, with echoes of other colors, or slight echoes of forms and shades. There is no deception or pretense here; this is a final destination of an honest quest, like a philosophical despair, visually unbearable; and Raffi Lavie – despite all my good will, I cannot share the excitement of some foreign critics vis-à-vis these whitish canvases, decorated with primordial drawn or incised lines, with echoes of pink or grayish tone. There is a type of endpoint of ‘total scorn’ for form and color, executed spitefully by an artist who is well capable of painting as well as drawing. Avshalom Okashi is faithful to monumental black surfaces, with torn, dramatic, white or orange pillars of light. This painting is certainly simplistic, yet undoubtedly impressive nevertheless.

It is rather among some of the younger artists that one finds values of truth devoid of sensationalism. In Moshe Kupferman’s works the abstract language has released an eloquence that attests to a true personality. His painting is like a confession, and is based on agitated, violent forms, intense colors, mainly gray-purple. The only canvas by Moshe Givati, a 30-year old kibbutz member, is interesting in its restrained, domesticated coloration manifested in free, ‘natural’ squares. Eliahu Gat’s watercolors are indeed formless, yet poetical, light, refined, like an abstract sea. Ury Lifshitz emerges as a painter in an intense whirlpool of mainly black and red ‘commas’ against a light background. It is an alert, pleasurable painting, influenced by George Mathieu (Haboker, 30 April 1964 [Hebrew]). Miriam Tal goes on to describe the works of Ziva Lieblich, Hayuta Bahat, Mina Sisselman (whose paintings appeared only in the catalogue), David Ben Shaul, Tuvia Beeri, Chaim Kiewe, Yehezkel Streichman, and Aharon Kahana. Her descriptions sketch the Israeli art world at the time – the withdrawal of the older generation (except for the prominent artists who continued to operate in different ways even after the disintegration of New Horizons) and mainly the root-taking of the younger generation of artist at the time. The Tazpit exhibition offered a blend of both generations, spawning, according to Tal, a non-homogenous result. Nevertheless she still found a set of interesting works, mostly by young artists, in it.

Joav BarEl referred to the exhibition held at the Helena Rubinstein Pavilion in his column “Exhibitions in Tel Aviv”:

Tazpit 1964 (Exhibition of Israel Painters and Sculptors – 1964) is unlike most group exhibitions with which the country has been blessed. First, it brings together 29 painters and sculptors, many of whom are among the leaders and shapers of the Israel plastic art scene. Second, it is not an exhibition organized ‘from above’ through external initiative, but rather the result of internal artist activity, in response to issues that bother them, taking artistic action toward a shared goal. The reasons that triggered the need for this exhibition are many; the most important of them are: 1) The participants’ shared belief that the only language which allows expression of the period in which we live is that of abstract art; 2) struggle against what the Tazpit members call a ‘speculative approach to art, trade in Jewish consciousness, use of symbols that have long lost their meaning, use of external impressions and depictions of objects and figures’; 3) the need for a common platform on which to present the fruit of their work ‘in apt light and with an uncompromising spirit’ (all the quotes were extracted from the group’s credo which opens the catalogue). In other words: the struggle waged by the Tazpit members is twofold: for exclusive expression in the language of abstract art, and against treating an art work based on the theme which it purports to depict.

BarEl concluded his essay by saying that:

The title Tazpit 1964 implies a Tazpit 1965. Such an exhibition can be a major event for all art lovers, and preparations for it should already get underway (Haaretz, 24 April 1964 [Hebrew]). This, however, was the first and last exhibition of the Tazpit group.

Exhibition of Young Israeli Artists: 1965

In the spring of 1965 I visited Givati in his studio in Sha’ar Ha’amakin (needless to say I didn’t realize then that one day I would seek the paintings he showed me on that visit in order to catalogue and exhibit them). He was wholly immersed in artistic work and the stormy occurrences in the art centers. My impression was that he stayed on the kibbutz solely for family reasons, and was awaiting an opportunity to leave. In Tel Aviv, preparations for the “Exhibition of Young Israeli Artists,” which opened at the Helena Rubinstein Pavilion in August 1965, were at their peak. It was decided that the participants’ age would range from 20 to 35. Haim Gamzu, the exhibition curator, explained the decision in the introduction to the catalogue: “By restricting the participants’ age we followed similar exhibitions in Europe, and mainly the precedent of the Parisian Young Artists’ Biennale.” In his essay Gamzu further noted:

Except for the odd ones, who took the ultimate risk in identifying with the most recent currents in Europe and America, the great majority of our young artists are often extremely cautious, overly so: – before they undertake to join any recent avant-garde ideology. Thus has arisen in them a sort of double mingling of influences; those who have been absent for a long period from an artistic centre abroad, and have not been confronted daily with the achievements and failures of the various innovators, and those who have come upon the neoteric abroad and under the shock of the modern, and the necessity for revision, have most radically abandoned their first way and taken new paths. It is therefore most important to summarize the achievement of those artists whose young age is generally a formative period, a period, simultaneously, of continuation and abandoning.

What characterises the artists represented in this exhibition is first the fact of their being, in most cases, either born, or at least, brought up in this country. Of like importance is the number of those belonging to the eastern communities, a fact which constitutes evidence of their becoming organically all one with the artistic creativity taking place here.

The exhibition was divided into three sections presented in three halls. The first featured mainly figurative paintings, the second – abstract painting, and the third – graphic works, figurative as well as abstract.

The “Exhibition of Young Israeli Artists” included 52 artists, among them Gad Ullman, Arie Azéne, Benni Efrat, David Ben Shaul, Mati Basis, Moshe Givati, Joseph Gattegno, Abraham Hadad, Zvi Tolkovsky, Amos Yaskil, Raffi Lavie, Yael Lurie, Ury Lifshitz, Mordecai Moreh, David Meshulam, Shaul Samira, Milka Chisik, Jacques Mouri-Katmor, Joram Rozov, Ivan Schwebel, Yitzhak Shmueli, David Sharir, and many others. Some persisted and continued to stand out in Israeli art later on in their careers, others later left the country, and yet others disappeared from the local art scene in the course of time. Joav BarEl was positively impressed by the exhibition, and wrote in his column “Exhibitions in Tel Aviv”:

In comparison to other general exhibitions, the “Exhibition of Young Israeli Artists” is characterized by high quality and multifacetedness. It displays a less dogmatic clinging to schools prevalent in Israel and a stronger emphasis on individual expression. This is not to say that the show does not contain exhibits that draw on certain schools – there are such exhibits, and the drawing on the lyrical abstract school so widespread in Israel is especially conspicuous – but even those associated with, or those that can be defined as part of the lyrical abstract school, emerge in the show in exhibits that are stamped with the imprint of self search and personal diversification. As aforesaid, the technical level is rather high, but equally important (perhaps even more) is that only a few of the participating artists display aestheticist ornamentation per se; the majority of the works display an emotional strength and the need to convey something meaningful.

BarEl, however, goes on to add a reservation:

Despite the general inclination to find independent paths, the exhibition contains virtually no echo of the radical-innovative quests that form a type of ‘avant-garde’ in contemporary plastic art… It may be highly significant that in an exhibition of young artists – who are, as usual, the first to respond to new trends – there is hardly any trace of assemblage, pop art, or op-art… In the department of abstract painting, the abstract geometric trend is conspicuously absent; apparently, young artists in Israel are not inclined to the unequivocal, highly rationalistic layout of geometric abstract (Haaretz, 13 August 1965 [Hebrew]).

Despite BarEl’s critical tone in this excerpt, however, he sums up his article with a decisive assertion: “The ‘Exhibition of Young Israeli Artists’ is one of the most interesting staged this year, and should be applauded.”

It is interesting to read Miriam Tal’s response to the same exhibition in Gazith, where she emphasizes a certain withdrawal she discerns in abstract painting:

… This is especially conspicuous in the graphics department, which usually surpasses painting in originality as well as quality. Even though the entire second floor was populated by abstract paintings, some of them good ones, and although there were fine abstract paintings on the other two floors as well, a transition is felt which is manifested in the mental climate. The painters faithful to vernal-lyrical, floral-lyrical, or desert-lyrical abstraction, usually teem with joie de vivre. The descriptive painters and graphic artists are usually immersed in total pessimism devoid of all playfulness, of any pretense. It is an authentic, ‘natural’ pessimism. To this atmosphere one should add, as a third, conspicuous fundamental, a profound yearning to find new ways and set themselves free of abstract conformism or descriptive conformity. Our young painters, for the most part, no longer settle for mere aesthetic solutions. Thus we come to the fourth fundamental underlying the exhibition: the quest for new paths leads to the world of the imagination, symbol, mystery, magic, enigma. This phenomenon has, as it is well known, many names, and in most cases it should not be reduced within the narrower frame called Surrealism. Hence also the surprising fact, that the works of these young artists are more akin to those of the Jewish École de Paris than to the ‘forefathers’ of our painting, especially the forefathers of abstract. When one sees youngsters filled with a revolutionary spirit and hot temper, but also with technique and knowledge, among them ones hailing from Iraq, Persia or the kibbutz, painting in the very tradition of Soutine, without imitation – it reinforces our belief in the continuity of Jewish painting with a definite ethnic character. This painting attests to ‘natural’ expressionist elements typical, as it were, of our people, which find a reasonable outlet, different than personal-lyrical or ‘cold’ painting. Man with his suffering and deliberations has returned to Israeli painting in either a symbolic form or realistic-stylized form (Gazith, vol. 23: 5-10, 1965-1966 [Hebrew]). Givati’s work, which was influenced by the school of abstract painting and its various forms, as well as the works of several additional artists who participated in the exhibition, did not match this description at all, which was, in any event, anachronistic and displayed lack of awareness of the occurrences and mindsets among the young artists in the mid-1960s. The “Exhibition of Young Israeli Artists” awakened the Tel Aviv street and created yet another link in a chain of organized exhibitions held in key places in the ensuing years, thus paving the way to transformations that later occurred in the Israeli art world’s approach to artistic exhibitions.

The Autumn Exhibitions: 1965-1970

Following the young painters’ exhibition, Dr. Gamzu planned to stage a similar exhibition of young sculptors, but the plan never materialized. Instead, in December of that year he initiated the first Autumn Exhibition. The group of artists he selected for that show indicated an attempt to please everyone, both mature and young, a tendency manifested in Gamzu’s introduction in the exhibition catalogue:

In the course of penetrating and comprehensive conversations that took place between artists and the management of the Museum, there emerged the firm conviction that this exhibition must be more sweeping and less sectarian in nature, for if this should prove of inherent value, it might well mark the turning-point in the relationship between Israeli art and the art-viewers who closely follow its progress. There was recognition of the need to endeavor to incorporate in the Autumn Exhibition the works of artists, some of whom had formerly been members of the ‘New Horizons’ and later the ‘Tazpit’ group, and others who have not aligned themselves with these organizational frameworks, but whose paths had been close to those of their colleagues who belonged to these groups; they include artists of the same age and those who are older, and also painters who participated in the Exhibition of Young Artists which was held recently in the Tel Aviv Museum.

It was thus that the idea of the Autumn Exhibition took shape, the outcome of the initiative taken by the Museum and the cooperation between it and the artists who are participating.

The list of participating artists indeed affirms the above. It includes painters and sculptors who were former members of New Horizons, alongside some of the young artists who participated in the Tazpit exhibition and the “Exhibition of Young Israeli Artists.” Givati was also among the participants, with two medium-size oil paintings. Scrutiny of Givati’s works from these years shows that he did not distinctively belong to the group of Lyrical Abstract painters, despite the assertion made by art critic Miriam Tal, that one could discern the clear influence of Zaritsky in his work. Givati’s works from that period articulate a constant struggle between the painterly trends prevalent in those years, and an outburst of powerful personal expression. His leaning toward figuration and his inclination for a geometrical division of the canvas, alongside occasional wild brushstrokes, preserved his unique expression which makes it difficult to affiliate him with a specific school of painting. Givati had been and remained an artist who absorbed from everyone, and in the course of time created a distinctive, identifiable painterly language all his own.

The Autumn Exhibition provided a counterpoint for the General Exhibition held annually by the Painters and Sculptors Association, which was a multi-participant exhibition shrouded in an air of anachronism and provinciality. Thirty-two artists participated in the first Autumn Exhibition (twenty of them were Tazpit artists). The eldest was the 74-year old Israel Paldi, and the youngest was around 28. Most of the works presented in the exhibition were defined by the critics as abstract art, although this was not necessarily the abstraction introduced by Zaritsky and his trailblazing colleagues. Among the participating artists, some turned to the type of abstract painting which had already been formulated in Israel and abroad, and already defined as “abstract academism,” to which they added elements with local motifs; others sought new ways to convey their personal perspective. Pinchas Abramovic, Mati Basis, and Moshe Givati presented abstract paintings with vivid, eye-capturing coloration. Similarly, the abstract paintings by Jacob Wechsler and Avshalom Okashi displayed an exceptionally colorful quality. Yehiel Krize remained faithful to the accentuated white element and the echoed cityscapes, Moshe Prupes’s paintings revealed flickers of red through ashen and silvery layers, with echoes of abstract star signs and the zodiac, and Moshe Kupferman presented impressive, tempestuous, grid-based canvases with warm coloration. Ziva Lieblich’s canvases were dominated by the desert motif, both as a theme and as a raw material, and Tuvia Beeri created a cosmic-symbolical-imaginary world in his colorful etchings. Elements of Pop Art were discernible in Aaron Witkin’s works; Ury Lifshitz presented dense, intricate canvases, and Raffi Lavie assembled segments of reality in paintings constructed as collages from newspaper and photograph shreds. Joseph Halevi combined an ethnic experience with more conservative values of abstract painting. Yehiel Kimchi presented striking, powerful visions in red-black combinations. Michael Argov founded his work on white surfaces. Aharon Kahana presented large, impressive canvases that drew on sculptural motifs employed in his ceramic work, and David Ben Shaul aroused interest with his post-abstract landscape paintings. The 70-year old Marcel Janco presented dynamic, angular aluminum reliefs that seemed to burst forth from his rigid drawing line. Joav BarEl featured two abstract reliefs of surrealist nature, both entitled Organic Landscape, created through a sharp interplay of gestures and strong twists, which acquired added depth by means of dark shadows on the one hand, and meticulous, calculated restraint, on the other. Yehiel Shemi stood out in the exhibition mainly by virtue of his welded iron sculptures: one was Homage to a Spaceman, and the other – Large Nest – a giant sphere cut in half which enabled a peek into its rusty complex mechanism. Buky Schwartz was surprising with elegant aluminum sculptures that displayed interesting, promising kinetic and optic experiments. Danziger created a cold-looking geometric sculpture reminiscent of a quintessential architectural structure which he dubbed The Ritual, and the young Pinchas Eshet presented closed, rounded, lumpy, crude and abstract powerful forms made of sheet iron. The late Aïka Brown was represented by a relief populated by ropes, sack cloth tears, and other elements that came together to generate a gloomy atmosphere. Israel Paldi presented reliefs consisting of primordial-eastern formations decorated with vivid colors. Dov Feigin introduced a new sculptural direction with sharp, symmetrical forms, like a game of variations with acute-angled triangles, and Lea Vogel presented The Wall – a daring work made of cardboard, comprising squares and rectangles, opaque areas and openings, with a few accents of dark paint and a touch of Pop. Aron Doktor innovated with an experimental work partly comprising ready-made elements; Hadar Frumkin presented sculptures made of crude basic logs, and Ori Reisman’s works were characterized by spontaneously primal compositions which he conveyed on canvas, attesting to mindsets like a seismograph. Moshe Mokady turned to a richer than usual coloration in his paintings, opting for a refined, light color gamut.

The first Autumn Exhibition stirred extensive reactions in the press and among art lovers. It was argued, for example, that all the participating artists stylistically belonged to the abstract wing in Israeli art, and thus the Museum intends to hold a separate exhibition of Israeli figurative art. The critics concurred that the exhibition did not display any new breakthroughs, and in this respect they regarded it as a sequel to the Tazpit exhibition. It was generally agreed that the “Exhibition of Young Israeli Artists” was better and had greater momentum than the “Autumn Exhibition.” The fresh, lively, angry spirit of the New Horizons group once again came up, gaining many superlatives in comparison to this mild organization. The large number of prominent artists who did not participate in the exhibition was also mentioned, and thus it was declared that it must not be regarded as a cross-section of contemporary Israeli plastic art, not even in the field of abstract. Mina Sisselman published an even more blatant review in Davar:

If we compare this show to the exhibition of Polish artists recently presented in the very same pavilion, we shall find that the Poles’ professional level exceeds that of the participants in the current exhibition. In the Poles’ exhibition one felt that they approached their work with solemnity, despite the fact that it did not display a single current, but rather included numerous artists from diverse trends. Even the exhibition of the seven artists from Brazil held at Dizengoff House on Rothschild Boulevard surpassed this exhibition in both artistic level and technical know-how (Davar, 24 December 1965 [Hebrew]).

In contrast, there were more positive views as well. Critic Reuven Berman, for one, was mainly impressed by the level of sculpture

in this exhibition:

The surprise in this exhibition lies in the fact that sculpture ‘stole the show.’ Both the mature and the young artists display fresh thought, knowledge, and daring (Al Hamishmar, 17 December 1965 [Hebrew]). Rachel Engel found the exhibition auspicious too:

While one still cannot say that this is a display of the best of Israeli painting and sculpture, for many of our prominent artists are not among the participants, and some of the participants are not among out prime artists, nevertheless the pulse of life is clearly felt here. It is a living creature, and if it gradually grows and improves, it has a good chance to endure (Ma’ariv, 10 December 1965 [Hebrew]).

Tslila Orgad directed most of her critical arrows at the provocative, defiant entrance hall, maintaining that it contained works that are “so anarchic and private, that they do not represent any specific current,” but praised the display on the third floor:

The display is more homogenous, the style – better defined, and it is not impeded by different levels of skill, but rather displays a homogenous artistic will throbbing in each and every artist: Givati, Basis, Kimhi, Abramovic (Yedioth Ahronoth, 10 December 1965 [Hebrew]).

Some wondered why artists like Zaritsky, Streichman, and Tumarkin were absent, if the Museum endeavored to display a cross-section of the “progressive” currents in Israeli art. Some of the critics, on the other hand, noted the reverberating impact of the kinetic-optical exhibition presented in Israel and the influences of Pop Art discernible in the exhibition favorably. They emphasized mainly the fact that it relied to a lesser extent on the brushstroke tradition and tended to be more communicative due to the artists’ use of diverse materials, symbols, and contents. Thus, although the exhibition drew much criticism, ultimately everyone praised “The Autumn Exhibition,” cautioned art lovers not to miss it, and even expressed a hope for fruitful continuation of this series of exhibitions. Indeed, “The Autumn Exhibition” at the Tel Aviv Museum lasted consecutively until 1970 (except for 1967 when it was canceled due to the war), and each year it brought in new artists who enriched its contents and provoked reactions in the local art discourse.

The 1966 exhibition was supplemented by names such as Aviva Uri, Alima, Michael Gross, Yehuda Neiman, Lea Nikel, Menashe Kadishman, Moshe Castel, Mark Scheps, Tumarkin, and others. All in all, it featured 39 artists, 18 of them new ones. This time too, Gamzu introduced a declaration of intent similar to that presented at the first Autumn Exhibition, explaining that the Museum’s goal in these shows was to diversify as much as possible between the different generations, to introduce innovations and surprise:

‘To assemble in one joint art display the works of artists whose common feature is not necessarily the homogenous social and personal element, but rather an artistic trend aimed at new aesthetic experiments and at variegated contemporary reactions, of which the innovation, far from being merely external, is an organic element of the spirit of the present age, its hopes, disappointments and rebelliousness.’ … In our time the borders between the figurative and the abstract have become blurred. The artist is no longer judged according to his leanings towards one trend or another, but on the intrinsic quality of his work, the nature of his personal or universal message, the communicative force of his art…

At the opening of the 1969 Autumn Exhibition catalogue, when the tradition was renewed after a one year pause, Gamzu referred to the important transformations that occurred in the path of certain artists, as well as to the implications of external influences on the local art. Forty-one artists participated in the show, some of them not having participated in previous Autumn Exhibitions. Among the seasoned artists who joined the tradition, one ought to note Zaritsky and Streichman (alongside Abramovic, Feigin and Baser, who had taken part in previous exhibitions), David Lan-Bar and Hanna Ben Dov, who were living in Paris at the time, as well as several new names, such as Avraham Eilat, John Byle, Yehuda Ben Yehuda, Reuven Berman, Yair Garbuz, Moshe Gershuni, Michael Druks, Hava Mehutan, Oded Feingersh, and Henry Shelesnyak.

The response to this exhibition was ambivalent. On the one hand, it sparked the critics’ imagination and elicited favorable, encouraging reviews; on the other, it also sparked harsh criticism, mainly aimed at the works of Moshe Gershuni and Yehuda Ben Yehuda. Miriam Tal wrote that:

Moshe Gershuni’s exhibits are of the entertainment type; these non-functional, red-yellow pieces of furniture do not belong in an exhibition; instead of plastic art we have here ‘the art of plastic’… Yehuda Ben Yehuda’s work invoked the question, whether the end justifies the means in the field of art as well. Via bodies cast in latex from live people, the artist ‘created’ a public of naked people, men and women, lying, standing or walking, at times trembling by means of an electric appliance. The end of days? Perhaps the resurrection of the dead. All interpretations are possible; the impression was rather appalling (Gazith, 26: 9-12, 1969-1970 [Hebrew]).

In this exhibition, Moshe Givati presented three large oil paintings of the same dimensions to which he reverted time and again over the years. Their compositions combined geometrical design with expressive motifs that conveyed a sense of horror and aggression.

The 1969 Autumn Exhibition opened in the absence of Gamzu, who was in New York at the time, working to expand the Museum’s activities and prepare for the opening of the new building. Thirty-six artists participated in that exhibition. Only a handful of them were new artists who had not participated in the previous Autumn Exhibitions, among them Rami Zohar, Daniel Peralta, Amichai Shavit, Michael Eisemann, Arie Aroch, Sioma Baram, Moshe Gringras, and Yeshayahu Granoth. As in previous years, the artists were selected by the Museum in collaboration with a three-member committee of “an important group of artists,” as Gamzu defined them (Joav BarEl and Alima were among the artists who sat in that committee over the years). Miriam Tal who reviewed the exhibition in her critical column in Yedioth Ahronoth, wrote:

Moshe Givati has turned pink, and he paints almost like Raffi Lavie several years ago, with hinted figures in light geometrical frames ( Yedioth Ahronoth, 5 December 1969 [Hebrew]).

The jury of the last Autumn Exhibition held in 1970 endeavored to lend the exhibition an avant-garde, current air. The 33 participants exhibited a wide range of artistic approaches. Some obeyed the criteria set out by the committee members and the challenges formulated by Gamzu at the beginning of the catalogue:

An art institution nowadays should, and some say must, provide information to the public concerning the various experiments which are being made in the field of artistic expression. This applies even if such experiments appear to be mere passing phases and even if some are doomed to failure. Certainly, it is only he who does nothing that risks nothing, but at the same time experiments which do not open up new aesthetic vistas, might lead art to a dead end. This Exhibition is experimental in character.

Indeed, the list of works in the catalogue indicated the experimental tendency among the artists, as well as the myriad techniques with which they chose to express themselves: Hena Evyatar created a work she dubbed Corals from a plastic material; Michael Eisemann processed a work entitled Oh, quell cul t’as from sewn cloth; and Michael Argov presented Modulation made of wood, nylon, and plastic. Joav BarEl created “Ho, those sweet sweet memories” in mixed media, Avital Geva set up an “industrial line,” 18 meters in length, and Yeshayahu Granoth created an object from fiberglass and metal. Moshe Gershuni presented Columns in mixed media, Ivan Moscovich – a group of dynamic objects in multimedia, and Raffi Lavie created Something in mixed materials. Shimshon Merchav presented 37 slides, Joshua Neustein – Road Piece made of straw and tar paper combined with sound, and Dida Oz presented Spring Love, a combination of oil and springs on plywood. Amihai Shavit presented Trauma, a work consisting of mirrors and wood; Buky Schwartz – Sculpture from Wall to Wall in colored plastic; and Eshet – Yellow Element made of shaped canvas. Alima used sponge-cloth for her work, and Henry Shelesnyak and Aviva Uri presented painting in mixed media.

Givati planned an installation for this exhibition that was supposed to consist of giant, transparent Plexiglas cube combined with a pile of paper sleeves. The latter were meant to fill the cube to its maximal height. The objective of the installation was to observe the pile’s sinking within the cube from the exhibition’s opening through its closing. The installation was planned in collaboration with a group of students at Haifa’s Technion who were supposed to take part in its mounting. While Givati’s name and a description of the installation indeed appear in the checklist, Givati himself recalls that he never participated in the 1970 Autumn Exhibition and the work plan never materialized, as he was drafted for 60 days of reserve service in Abu Rudeis.

The Autumn Exhibition tradition was stopped upon the opening of the Tel Aviv Museum’s new building on King Saul Blvd.

10+ Group: 1965-1966

The 1960s were characterized by organizations of artistic groups aimed at gaining power in order to pressure the artistic establishment, and mainly the Tel Aviv Museum and its director, Haim Gamzu. Raffi Lavie was the life and soul, the mover and go-getter behind the organizations of those years, and his influence in the field of Israeli art since the early 1960s swept the young generation of artists along – first those born in the 1930s, and subsequently the younger as well. Concurrent to the “Tazpit” exhibition, the “Exhibition of Young Israeli Artists,” and the “Autumn Exhibitions” (where the impact of the “new winds” that blew in the establishment’s face in full force was conspicuous), the 10+ Group was also established, perceiving its organization mainly as an impresario-like step; the group members decided to present their works together and invite guest artists to take part in their exhibitions. The idea of establishing the group originated as a response to the intrigues and plots in the selection of artists for the “Tazpit” exhibition. The idea was conceived by Aïka Brown and Raffi Lavie in 1964, but Aïka died in a car accident in France that same year, and the group’s founding was postponed a year. The group included Raffi Lavie, Tuvia Beeri, Mati Basis, Buky Schwartz, Pinchas Eshet, Ury Lifshitz, Siona Shimshi, Joseph Gattegno, Benni Efrat, and Malka Rozen. Givati himself belonged to the “+” rather than the “10.” Various artists were invited to take part in the exhibitions initiated by 10+ in the spirit of the policy introduced in the group’s codex formulated in Raffi Lavie’s apartment in August 8, 1965. The group’s aim was not to attack the artistic establishment, but rather to operate by its side and even assimilate into its various activities. Among their achievements, the group members managed to force the Tel Aviv Museum to add Ury Lifshitz and Mati Basis to the “Exhibition of Young Israeli Artists” despite the management’s objection. The group members strove to be original at all costs. They wanted to surprise, shock and shake the local art milieu, provoke and elicit a debate. The ten exhibitions they staged were given thematic titles and did not serve any ideological trend. They evinced the influences of Pop Art, and were typified by extensive use of diverse materials. The critics blamed the group for its inclination for gimmicks. Ultimately, during its five years of operation, 10+ furnished some 70 artists with a platform, whereby to reach the consciousness of the local art milieu, thus helping to fight the stagnation that permeated the art world, setting it free and promoting it.

The first exhibition of 10+, “Painting on Textile,” opened in December 1965, featuring fashion textiles painted by artists. It was held in the Maskit shop on Ben Yehuda Street, Tel Aviv. The critics mocked the exhibition which tried to tie painting and textile design – specifically, they laughed at the fabric dimensions which were matched for cutting dresses and shirts, and did not refer to the breakthrough introduced by the artists when they brought art down from the Olympus to the street. The members of the “10” who participated in the exhibition were Raffi Lavie, Siona Shimshi, Buky Schwartz, Joseph Gattegno, and Malka Rozen. The “+” was represented by Moshe Givati, Aaron Witkin, Nora Frenkel, and Dani Schwartz. Givati was given ten sheets of cloth by the Kibbutz sewing workshop, and painted on all of them in a special ironing technique (the dyes were supplied by a company for textile dyes, through the initiative of Siona Shimshi, who was Maskit’s tie-dye artist). Once the fabrics were removed from the shop’s ceiling where they had been suspended, Givati gave one painted fabric as a gift to Emma, Pinchas Abramovic’s wife, from which she made herself an original evening gown that she wore for a gala concert of the Philharmonic Orchestra. Givati returned the remaining fabrics to the sewing workshop at Sha’ar Ha’amakim, where they made fashionable summer dresses for the female members. Fashion designer Jerry Melitz also used the painted fabrics to make unique dresses which were presented on the opening night of the second 10+ exhibition, and this time they were lauded by the critics.

The second exhibition of the 10+ group was entitled “Large Works” and held at the Artists’ House on Alharizi Street, Tel Aviv, in February 1966. The participating artists were asked to prepare works more than 2 meters in height. Seventeen artists took part in the show; some of them had no previous experience with such large-scale works. On the opening night the artists surprised the audience with a monumental collective piece installed before the audience as a live performance. It was the first time such an act was held in Israel, and it stirred up the artistic community. Concurrent with the exhibition there were also poetry readings, concerts of electronic music, film screenings, and theatrical performances. After the closing, the works were sold at an auction conducted by Dan Ben Amotz.

The exhibition stirred interest in the local art milieu, but the critics were in disagreement. Joav BarEl criticized some of the works, but wrote favorably about the exhibition as a whole:

While one may disagree about the quality of certain exhibits, there is no argument about one thing at least: the exhibition is not boring. For the first time one may clearly encounter echoes of the artistic shades now occupying such an important place in America and Europe – Pop Art, the object, art where the spectator takes an active part, etc. It is a fresh manifestation that must be congratulated – even if it is somewhat later than similar activities abroad, at times much more radical. Individualism stands out in the exhibition. At the same time, groups come together of their own, which may be classified according to the means of expression and its orientation (Haaretz, 25 February 1966 [Hebrew]).

In this context BarEl classifies Givati, Basis, and Gattegno in one stylistic “group” of which he writes the following in the same article:

Mati Basis, Moshe Givati, and Joseph Gattegno, each in his own path, construct their works in more conventional techniques that contain clear echoes of the expressionist-lyrical abstract. Despite the large format, the three have managed to create exhibits that are among the most beautiful of their works; Gattegno is colorful and rich, Basis is freer and braver than ever in his brushstrokes, and Givati is more accurate here than in any of his paintings in the past.

In his article BarEl reviews the works of all the exhibition participants where most of the 10+ group members were featured (save Tuvia Beeri and Ury Lifshitz), alongside the added artists whose number was larger than in the past. In contrast to BarEl, critic Tslila Orgad maintained that the exhibition displays “vulgarity in the guise of art”:

It is usually possible to make amends for the fact that an artist employs the style of a foreign colleague, presenting it to his provincial peers as his own creation and vision – if that style serves as a mere vehicle and means, rising to the level of a work with a new, subjective meaning, one adapted to his own ideology. Unfortunately, this is not the case with some of these artists, who display all the ‘Pop’ and ‘Op’ and every other ‘ism’ now prevalent as painting’s latest trend in Europe’s capitals and in the USA. Lack of independent thought, detachment, pure avant-garde, excessive (inauthentic) tendentiousness, a type of propagandist-superficial showiness – this time these characterize the works by Segré, Lavie, Weinstein, Witkin, Doktor, Malka Rozen, and Buky; I am particularly appalled by the naked truth as revealed in the large mural painted by all the participants on opening night: for some reason it reeks of screeching – albeit without artistic perspective – of hit parades, and other mass psychoses, brush splashings, paint dripping on the ground, children’s wall scribbles (Yedioth Ahronoth, 25 February 1966 [Hebrew]).

Rachel Engel, in Ma’ariv, summed it up laconically:

They call their exhibition ‘Large Works’ – and it is unclear whether this refers to the works’ physical dimensions or rather to their artistic value. Coming to observe the exhibits we have indeed found one monumental surface called a ‘group painting’ created by the 10+ members on opening night, as well as other unusual exhibits of rather large dimensions, but the largeness did not manifest itself in the spiritual qualities as well (Ma’ariv, 25 February 1966 [Hebrew]). Reuven Berman, who later joined the group’s exhibitions as an artist, wrote in Al Hamishmar:

We witness an exhibition of Israeli art, where the reflected perceptions chronologically correspond with those dominating avant-garde art in the rest of the world. Here we have a group of young artists who at the very outset of their artistic maturation practically identify with the main artery of contemporary art. Since the predominant perceptions in the exhibition were formed via ‘guidance’ originating outside Israel, and were in part brought here directly by some of the 17 participants, who only recently finished their studies, training, or work periods in Europe, the artists participating in the exhibition have reached a crucial crossroads. The participants, as well as several other artists who did not participate in the exhibition, but whose work mode is closer to the perceptions and currents represented in it, will have to decide – whether to continue obtaining guidance overseas and keep their works ‘abreast of the time’ (thus creating a modern version of that provinciality against which they fight with all their strength), or to speak the art language of their period articulately, yet introduce into their works a personal shade and original thought that would reflect their personalities as well as their physical and spiritual setting. Only the second option may enable these young artists to transform the affinity with international art into a mutually productive link (Al Hamishmar, 25 February 1966 [Hebrew]).

From here Berman goes on to describe the works, relating, inter alia, to Givati’s work:

In the excellent paintings by Givati and Gattegno, these two artists arrived at new achievements. Givati frees himself of Zaritsky’s strong influence and his deep, mysterious painting.

Unlike other critics, who mockingly describe the young artists’ “imitated caprices,” BarEl and Berman wholeheartedly encourage the external influences. Their stance stems from the recognition that Zaritsky’s dominant impact has been so crucial, that it went beyond his own generation and continued to reverberate vigorously in the artistic perception of the young generation of artists, causing the young local art to run in place and shut itself off from new trends. Thus the influence of the currents that stirred up the US and Europe at the time and shaped Western art was restrained, and they remained outside the local arena far too long. Givati assimilated, in his own way, the values of “Lyrical Abstract” a la Zaritsky (which was a local version of sorts of the French informale and American Action Painting, yet more subtle and introverted, amorphous in its color and texture, more “breathing”). Now, however, he began setting new challenges for himself, opened himself up to new, additional influences, and strove to develop and consolidate his own painterly language.

When Givati was invited to participate in the exhibition “Large Works,” he painted three very large-scale canvases. Hanna Ben Dov, who stayed in Israel at the time, visited him in his kibbutz studio and chose one of them for the exhibition. Givati brought the work to the Artists’ House, and from there, went off to “Puerto Rico.” (A delicatessen and bar, a meeting point of the Tel Aviv bohemia). When the exhibition was wholly mounted, he discovered that due to lack of wall space, his work and that of Gila Zur were installed as partitions within the exhibition. He disapproved of the hanging mode and decided to remove his painting, and Zur soon followed suit. When Raffi Lavie heard about the incident, he sought Givati at the Abramovics, and Emma called Givati in Puerto Rico. Eventually, Lavie installed his own work in the buffer zone originally allotted to Givati, thus solving the problem. Zur’s work, which was later praised by the critics, was given a more suitable place as well, and the incident was resolved.

The 10+ members were most active in 1966, when they organized two additional exhibitions: “Miniatures” held in October at Gordon Gallery and “The Flower” held in December at Massada Gallery. Among the artists who participated in these exhibitions were Alima, Bianka Eshel-Gershuni, Batya Apollo, Mitchell Becker, Nora Frenkel, Menashe Kadishman, Shmuel Buck, Dani Karavan, Henry Shelesnyak, as well as artists and art critics Nissim Mevorach, Reuven Berman, and Joav BarEl. In the following year, in “Exhibition in Red” held at Katz Gallery in March 1967, and the exhibition “The Nude” at the Gordon Gallery in November that year, they were joined by artist-critics Mina Sisselman and Ran Shechori, as well as young artists Yair Garbuz, Aviva Uri, Jacques Mouri-Katmor, Jocheved Veinfeld, Miriam Tovia, and others. “The Nude” scored favorable reviews and gave art collectors an opportunity to purchase works for relatively low prices.

|