| Hana Kofler

The Summer ‘70 Exhibition

Givati ended the 1960s with a solo exhibition at Goldman Gallery. He began the 1970s with intense activity in Haifa. He did not cut himself off from Tel Aviv, which continued to function as the central axis in his life, but endeavored to shift some of the current, updated feeling of the central city to the peripheral Haifa, which in those days was dominated by the Haifa Association of Painters and Sculptors, the sole authority that determined the exhibitions and contents to be presented locally. Thus, in the same month when 10+ staged its last show in Tel Aviv, the “Summer ‘70” exhibition opened at Gan Ha’em Park, Haifa. Givati initiated and produced the exhibition, and Shmuel Bialik, Head of the Culture Department at Haifa Municipality, gave him full backing and support throughout the production of this artistic endeavor which went beyond anything the northern city had been accustomed to theretofore. The press discussed Givati’s event as “a breath of fresh air.” The participating artists included Joshua Neustein, Yocheved Weinfeld, Buky Schwartz, Eli Ilan, Michael Argov, Aviva Uri, Michael Eisemann, Michael Druks, Pinchas Eshet, Ran Shechori, Henry Shelesnyak, Zvi Mairovich, Raffi Lavie, Ruth Cohen, Moshe Gershuni, Joav BarEl, Dan Levin, Shlomo Selinger, Shlomo Cassos, Itzhak Danziger, Michael Gross, Yehiel Shemi, and even Zaritsky. Raffi Lavie assisted Givati with the artist selection, and Danziger helped with the works’ installation and hanging. The Mayor of Haifa, Moshe Flimann, opened the exhibition, and Joav BarEl spoke on behalf of the artists. Art critic Zvi Raphaeli (Haifa-based himself), expressed his excitement:

The ‘familial’ General Exhibition of Artists of Haifa and the North has passed away at a ripe old age. Through the private initiative and sole authority of one of the non-establishment artists, and with the Municipality’s full support, a nation-wide exhibition was organized for the first time 9Haaretz, 9 October 1970 [Hebrew]). The papers further noted that the selection finally deviated from the provincial atmosphere prevalent in the ordinary exhibitions held in the city, and from considerations of peace-keeping in the Association, protecting the ‘rights of veteran members,’ giving in to various pressure groups, etc. Sculpture exhibitions had previously been held at Gan Ha’em, but this time the pavilion that remained from the flower show was used for mounting an exhibition of paintings and for presentation of works intended for interiors. The reviews about the quality of the works were mixed. Some perceived the exhibition as an opportunity to exhibit seasoned artists from among the members of New Horizons (two of whom participated in the exhibition), and voiced their hope to see more of their works alongside those of young artists that generally populated such exhibitions; everyone, however, wished for a fruitful continuation in the same spirit, and regarded the unusual initiative as a breakthrough as far as presentation of art works in Haifa was concerned.

For the mounting phase, Givati collaborated with Danziger who taught three-dimensional design at the Faculty of Architecture in the Technion, and resided in Haifa. At Gan Ha’em, Danziger himself featured the sculpture Light, comprised of four formal syllables whose combination generated a structure that refracted and reflected the light. The sculpture was made of steel cylinders painted white, blue and red, and linked in their top parts by means of rectangular surfaces of industrial metal painted white, calling to mind wings pulling upwards to the heavens. These were, in turn, connected to thin pipes painted white, and the entire construction created a type of drawing in space exposed to the sunlight and its motion. The structure cast shadows of varying degrees of brightness on the sculpture and the surrounding ground. The large-scale sculpture made its debut at the Tel Aviv Exhibition Grounds; subsequently, in the “Summer ‘70” exhibition in Haifa, a new and more sophisticated version of the sculpture was presented, including metal scraps contributed by the Shemen factory through the mediation of Benjamin Givli. The sculpture was disassembled at the end of the exhibition.

Givati himself presented paintings in acrylic on canvas, where he displayed measured use of black-gray-white hues that accentuated the geometric precision created on the surface, and merged with free brush strokes devoid of meticulous planning.

Rehabilitation of the Nesher Quarry Project: 1970-1971

Givati first met Danziger in the 1960s, in the “Tazpit” exhibition, and subsequently in the Autumn Exhibitions. Their initial acquaintance was made in encounters at the Herlin café on the corner of Dizengoff and King George Streets in Tel Aviv, where the artists used to pass on their way from the Helena Rubinstein Pavilion. “We used to sit there and talk. This was how Danziger found out that I lived in Haifa. He had just come back from Düsseldorf thrilled from the encounter with Joseph Beuys.” Danziger had already engaged with “landscape structures,” “transient, ephemeral sculpture,” and ideas originating in the affinities between natural qualities and human qualities, back in the 1960s. In Europe he found extensive echoes of the ideas that preoccupied him, came across far-reaching developments in the field of environmental art, and attended discussions of ecological issues which had been evolving throughout the world at the time. In November 1970 he was invited to present his work Suspended Artificial Landscape in the exhibition “Concept + Information” that opened at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, on February 2, 1971. This work was the first harbinger in the gradual realization of his future plans: on a floating square surface he scattered a blend of paints, plastic emulsion, cellulose fibers, and chemical fertilizer. With artificial lighting and irrigation the first signs of germination appeared on the surface. Transparencies projected next to the suspended work presented the environmental ecological damage caused by landscape-destroying industrial plants and air-polluting transportation hazards. Concurrently, Danziger sought a suitable platform to realize his ideas, aspiring to create a monumental environmental piece.

Photographer Shosh Reich arrived in Israel from the USA at the time, and Joav BarEl brought her to Haifa. Influenced by Danziger’s talk about earth art, Givati sought ways to realize ideas in that field. As a point of departure he asked Reich to photograph the retreating waves at the Bat Galim beach and the traces and forms they left on the sand. From these photographs Givati later created a series of unique works in screenprint technique. Subsequently, Reich also photographed expressionist moments on the football pitch at Kiryat Eliezer for him to paint. The two situated themselves by the goal in order to capture human situations and thrilling moments during the game. The series of works which Givati had planned according to Reich’s soccer photographs, however, never materialized, as he recalls:

Danziger came to visit me at home, at Shoshanat Hacarmel. We discussed ideas and plans at length. One evening, on November 27, 1970, we both got an urgent phone call from Joav BarEl, who told us to turn on the television. In the news program ‘Events of the Week’ they showed Avraham Yoffe, Director of the National Parks Authority, and Yehoshua Raz, CEO of Nesher Ltd., in a TV debate about the fate of the deserted quarries on the western slopes of Mt. Carmel. The massive quarrying enterprise entirely thinned them out of the stone reserves required to produce cement. The press at the time harshly criticized the Nesher plant for the pollutants it discharged into the air, despite the special filter attached to the factory’s smokestack. In effect, however, the filter slowed down the cement manufacturing process, and thus was not often activated at all. The plant also wanted to gnaw away at additional parts of the Carmel for quarrying a chalklike substance. Joav BarEl, a “man of ideas,” instantly linked Danziger’s aspirations with Nesher’s image-building needs, and conceived of the project of rehabilitating the deserted quarry. Danziger had already been in touch with specialists and professionals from the Technion at the time, and they helped to explore different methods for reclaiming the place. I knew the Nesher CEO, Yehoshua Raz, and immediately organized a meeting between them. Four days after the TV debate, in a meeting held in Raz’s office, the ‘Rehabilitation of the Nesher Quarry’ project was launched. Danziger talked about hanging gardens, and I proposed to issue an international tender for architects and link the rehabilitation with the construction of a residential neighborhood. We started touring the quarry areas, and in one of them, which was adjacent to the factory and looked just like the surface of the moon, we discovered a green patch in the middle of the wilderness. It was difficult to climb up there, but as we approached, we discovered that the wind had carried some barbed wire fencing which became fixed in place up to that spot, and around it gathered scraps of paper and various types of drift in the course of time. Seeds blown in the wind were stopped by this obstruction, sprouting between it and the thin chalky layer that remained there, and pioneer plant species began to colonize that bare spot of ground. Hence we learned that there was no need for relief workers to recreate the landscape, but it could be achieved instead by much simpler means, because nature can take care of itself.

Nevertheless, rehabilitation of the site demanded preparation of an infrastructure, a process which involved planning rock explosions, creating depressions and craters in which the earth would be concentrated, moderating various gradients, scattering nets, preparing habitats for plant cultivation, seeding and strengthening the vegetation, and perennial maintenance which would involve observations and experiments intended for improvement and optimization. The Nesher Company was willing to take all the expenses involved in the rehabilitation upon itself. Raz knew that if the damaged slopes were rehabilitated, the company would be able to continue quarrying stone from the mountain.

Givati participated in all the stages of the experimental rehabilitation of the Nesher Quarry, from the moment in which the idea was conceived to the phases of practical execution. In the planning phase he suggested to Danziger to photograph every phase in the work and document it by means of screenprints. Danziger liked the idea, and Givati approached a master-printer who worked in Itche Mambush’s screenprint workshop in Ein Hod at the time:

I told him that we wanted to document a project. We made a deal and agreed that he would come to work as subcontractor. We set up a workshop in my apartment in Shoshanat Hacarmel, and the place became a screenprint workshop and an office. Danziger used to come every morning to make phone calls and deal with the quarry issues. It came to the point that I moved my family out and rented another apartment for them. Itzhak and I often drove off to the quarry in his Morris station-wagon. It was winter, and we used to come back in the rain and mud.

Givati who had finished working on the series of works after Shosh Reich’s nature photographs, now devoted himself to a series of works in other media (acrylic on canvas, mixed media on paper, screenprints, drawings), all of which pertained to the quarry. The theme was burning in him and provided him with extensive material for a new outburst of creativity. The rehabilitation project got underway, the ecology specialists from the Technion remained on site, and the activity was intense. The press began to moderate the harsh criticism previously aimed at Nesher due to the latter’s willingness to collaborate and find solutions for the acute ecological problem. In January 1971 Givati had already decided to exhibit his new works at Mabat Gallery, Tel Aviv. Danziger, who had presented a large series of drawings there a year earlier, was the exhibition curator and was entrusted with hanging the works in the Gallery. In that exhibition Givati featured two large-scale canvases and a series of works on paper. His drawings evinced a light, lyrical atmosphere. Soft gray pencil stains blended with a refined color drawing and dissolving textures in pastel hues. One can trace an affinity between these works and Larry Rivers’s painterly approach, essentially based on virtuoso-free expression of the accomplishments of free abstract. Inspired by this approach, Givati incorporated figurative and graphic elements in the colorful texture using various technical means, such as pencil, oil pastels, brush and Indian ink, all on a single sheet of paper.

On January 15, 1971, all the papers published reviews of Givati’s exhibition at Mabat Gallery, and all of them discussed the fact that Givati was a full partner in the quarry’s rehabilitation process. Tslila Orgad, for example, wrote:

Nesher’s deserted quarries, which have left a big, barren scar in the landscape of the Carmel, are now, as it is well known, the worry of National Parks Authority Director, Avraham Yoffe, and all those ‘Beautiful Israel’ enthusiasts. Several artists such as Danziger, BarEl, and others, and apparently Givati as well, have recently come together to find a landscaping-architectural solution to revive them. In the meantime, the desolation has not bored Givati, and has inspired him to create an extensive series of abstract color drawings in pens as well as thick black brushes. The tendency is coordinatory – relationship between hatched areas, stains dissolving like dust, horizontal lines, hinted objects in the horizon, and chiaroscuro (Al Hamishmar, 15 January 1971 [Hebrew]).

Ran Shechori further added in Haaretz that:

Givati’s drawings are a free, imaginary depiction of a realistic fact – the quarries of the Nesher plant on Mt. Carmel. Under his treatment the theme has undergone many processes of reworking and painterly styling, and only little of the realistic image remains in the final product. One must perceive his drawings as free sketches for the challenge in which Givati takes part – the rehabilitation and reconstruction of the Carmel landscape, destroyed by the quarrying. His impressions form a type of pre-documentation for a large-scale enterprise, enabling an artist to deviate from the boundaries of the paper or Museum space, and create on the scale of landscape and nature itself. This thought, evolving in the consciousness of contemporary art for several years now, strives for the creation of ‘cosmic’ art whose means are drawn from nature and from advanced technology, its dimensions are superhuman, and its place is in nature itself. Christo’s enterprise in Australia and similar attempts made in the USA, Germany, and England, seem to open up a new artistic era. One must view the fact very positively that in Israel too, there is someone willing to allow such artistic-architectural-technologic experiment (Haaretz, 15 January 1971 [Hebrew]).

This was Givati’s seventh solo exhibition, and Miriam Tal, in her review, emphasized that it was a landmark in Givati’s evolution as an artist. She referred mainly to the smaller drawings which she deemed the most succinct and sensitive:

The current series certainly marks advancement toward formal concentration, a personal idiom and painterly culture. These are brush and stylus drawings; and there are also some papers where color is added by means of pastels or colored ink. The artist seems to succeed in articulating himself more convincingly in smaller paintings. According to him, several of the paintings were inspired by thoughts and proposals for the rectification of the landscape following its inevitable destruction, such as for the construction of quarries. Violent yet aesthetic, overly defined, the forms are concentrated at the center of the paper or canvas. The structure is diagonal, or alternatively based on a horizontal-vertical dichotomy. The white background is prevalent, but not exaggerated. Several sketchy paintings virtually convey the impression of abstract photographs, but there is no trace of photography here (nor of collage), and everything is achieved exclusively by means of drawing (Lamerhav, 15 January 1971 [Hebrew]).

A similar impression was also reported by Mina Sisselman in Davar:

The theme of the exhibition: new impressions from the quarry in Nesher, near Haifa. The subject seems to have occupied the artist for a long time, and the results of his impressions are seen in the multiple drawings he now presents. Most of the paintings are executed in black-and-white, sharp stains and continuous lines. In some instances the stains are scattered, leaving white gaps between them, in others – blots are grouped together, generating rocky lumps. Occasionally there is a scribbling in red or blue that assimilates into the black drawing; the color adds softness and a picturesque atmosphere. The drawings are variously sized, some – quite monumental, but it is in the smaller drawings that the artist seems to arrive at greater encapsulation than in the larger ones (Davar, 15 January 1971 [Hebrew]).

Reuven Berman presented a different view in the art section of Yedioth Ahronoth:

The smaller works related to the quarry motivation tend to be studied rather than full-blown position. Other works on paper, mostly drawings, are purely abstract ‘scrawl and scribble’ images (Yedioth Ahronoth, 22 January 1971 [Hebrew]).

Like other critics, Berman also relates at length to the background story underlying the exhibition:

The show is an outcome of an unusual joint project Givati has been working on with sculptor Itzhak Danziger. They have been considering ways of solving one of the Haifa area’s most prominent eyesores, the Nesher Cement Co.’s quarry that continues to eat into the flank of the Carmel. The idea is to base the work at the quarry on an overall carving plan that would result in a sort of landscape sculpture, to be topped off by plantings, and eventually turned into a park – a fine and original solution to a problem about which ‘Israel Beautiful’ enthusiasts have rightly raised a furor.

The paintings are impressions on topography and geological structures, many of which also include visual thinking out loud on organization solutions. As paintings they rely entirely on the contrast of geometric qualities with organic painterly ones, and Givati truncates areas and inserts straight lines and angles into the relatively amorphous masses with considerable sensitivity. The large paintings are made of several smaller canvases joined together and can be reassembled in other combinations. … Givati also showed me a photograph of a painting comprising elements from two different paintings, and the result appears perfectly harmonious (Ibid).

Ostensibly, Givati underwent a transformation since his previous exhibition at Mabat Gallery (May 1969), where he featured works distinguished by their multiple elements: contrasting coloration, influences of geometrical abstract or Pop, pure figuration, incorporation of photographs, eruptive expressivity, etc. In the current exhibition only strong, sensitive pencil lines, geometric structuralism, free brush strokes, and reasoned stains remained – elements that came together to form an abstraction of landscape.

When the exhibition at Mabat closed, art patron Menahem Yam-Shahor, who had previously purchased works from Givati, came to the Gallery, loaded all the unsold works into his car, and mounted an exhibition in his home in Ramat Hasharon. Yam-Shahor and his wife printed invitations and hosted the guests at the opening. All the works were sold that very day, and thus the quarry series was distributed among multiple collectors. In the meantime, plans and works in the quarry site on the slopes of Mt. Carmel continued. Danziger consulted additional specialists for quarrying, gradients, and explosions on site. Nesher CEO, Yehoshua Raz, came to lecture students at the Technion. Together with ecologist Ze’ev Naveh, and land researcher, Joseph Morin, he also lectured before public officials. Danziger also harnessed his students at the Technion for practical work on site, as part of the large team of rehabilitators which also included a PR adviser. Givati wanted to bring additional artists into the project, and set up a company to promote the idea of a residential center at the heart of the quarry, but Danziger did not operate in this direction. Only toward the end of the experimental phase – following the explosion intended to level the area, and the site’s preparation for planting and seeding, was the final rehabilitation model formulated, which included all the functions – construction, industrial area, roads, etc. Joav BarEl, who had in fact conceived of the entire project and was its ideologist and theoretician, started teaching at the Technion that year. He was supposed to photograph and document every phase in the rehabilitation enterprise, but decided to resign from the project at the outset of practical work on site.

As the work in situ progressed, Givati also realized that the project was going to yield nothing practical, as was originally planned, and that all that remained of it was “the experimental rehabilitation of a select site in the area of a deserted quarry, as planned and executed by Itzhak Danziger, Joseph Morin and Ze’ev Naveh.” (This was how the documentation of the process was described in a catalogue produced through the support of Nesher Portland Cement Works Ltd. and under the auspices of the Israel Museum, Jerusalem. The introduction for the catalogue was written by General Avraham Yoffe, Director of the National Parks Authority, who also opened the exhibition of the Quarry Rehabilitation Project at the Israel Museum, on May 28, 1972). He was summoned to a law office in Tel Aviv to sign a document stating that he had no conceptual rights over the Nesher project, and after a long conversation with Danziger, accompanied by a fair share of alcohol, he was forced out of the project as well. The “model rehabilitation” was completed on November 21, 1971, as some thirty different plant species struck root and germinated, making the area green. Danziger thought that dissemination of data about the experiment was as important as the experiment itself. His final conclusion was that the most appropriate solution for the site would be designating the quarry area for construction due to its proximity to residential and industrial areas, and that every construction process would inevitably involve destruction of the natural landscape.

Haifa: 1970-1974

Givati, who was left with a screenprint workshop and debts from the quarry project, fell into severe dejection. At that stage he devoted himself to production of prints of his own works, as well as for Mairovich, Shmuel Katz, Michael Gross, and even Reuven Rubin. Prof. Avram Kampf, Head of the Art Department at the University of Haifa visited his studio and stayed there for an entire night. Following the visit he offered Givati a post as guest lecturer in the Department. In addition Givati taught art courses for gifted children in the Technion.

Givati’s syllabus at the University was intended to supplement the artistic education of junior high-school teachers and of ordinary students. According to him, during the only year in which he managed to hold a position in the institutionalized world, he used to play with his students and conduct extensive experiments with them, but made no effort to teach them academic drawing or painting. On one occasion he ordered a ton of flour and 40kg yeast. The flour was poured in the center of the classroom, creating a flexible pile whose contours changed with every motion. The students were asked to observe the abstract forms generated by the flour and try to draw them. As part of another exercise, Givati asked the students to fold a sheet of paper into a ball:

Everyone laughed and there was already good atmosphere. Then I told them to open the paper ball, extend it and observe it. I explained that they had created a topographic entity. On the surface of the creased paper I told them to draw in soft pencil or in pastels, at their will. We later developed this exercise without creasing the paper. They arrived at very good results in drawing. We never did anything with the yeast. At the end of the academic year I planned to pour all the flour on the floor, mix it with the yeast, and let it rise to the ceiling and block the entire room. We simply never got to it because I was dismissed before that. Among other things, I asked them to find an old chair at home and paint it with oils. I explained that artistic painting was primarily a painting job, and then I taught them what painting was. Then, one winter day, I took them to the forest. We gathered mud and returned to the classroom. We painted with the mud and in pencil. At first they were quite amused, but then they started working passionately, created earth paintings and obtained very interesting results. In another instance I asked them to bring pebbles from the beach to class. The exercise was to fold half a printer’s sheet in four: on one side they were asked to write, in their own words, what colors they found on the pebbles. They could give original names to these colors, any color name that came to mind. Then they outlined a square the size of a floor tile at the center of the opposite quarter, delineated it with masking tape, and were asked to paint all the colors they had seen in the pebbles within the square. I think they created real jewels of abstract painting.

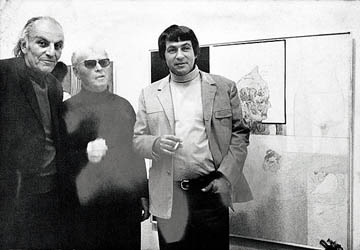

Moshe Givati, Zvi Raphaeli, Kuba Leibl, Goldman Gallery,

Haifa, 1970

Givati had an American nude model named Sandy, who Hebraized her name to Holit. She was his wife’s best friend. Both were active in the Women’s Liberation League in Haifa. Holit used to model for Givati in his studio, and he also brought her to model for his students in University:

When we started working with a model, I made all kinds of experiments on her. I wrapped her body in nylon and tied it with ropes. The students had to draw her body as it appeared through the creased nylon. In fact, they had to treat the entire mass, and not only the body itself. Eventually they didn’t try to depict Holit, but rather some concept of her. There we also did the first experiments in printing a human body on canvas. Holit would smear her body in baby oil, and then with a thick layer of paint, and I would then press her entire body onto the canvas. Removing the paint from her body was a different story. I had to become sophisticated, and instead of cotton wool to remove the paint, I used leftover cotton fabric that I bought in sacks from some factory. Once we used turpentine, which scratched her skin in sensitive places. There were terrible screams. At the time I was working on a monumental canvas that Goldman from the Gallery wanted to present in an exhibition organized by Shimon Avni and Alima, where Raffi Lavie and several other Tel Aviv artists also participated. Holit quit in the middle of the work. Alima, who just arrived, stripped instantly, we smeared her body with oil and paint, and the print of her body was born on the giant canvas suspended that very day on the central wall in Goldman’s gallery.

Givati’s teaching mode was incongruent with the conventional mode, and the University authorities were dissatisfied. He once asked for clay to be brought from the Ceramics Department, then ordered his students to create balls from the clay, throw them forcefully against the wall, and refer to the textures they left on it. At the heat of the exercise several windows were broken. It so happened that during that very lesson Kampf came into the classroom with a group of donors from Germany, and the drama into which they chanced obviously appeared like an illusive theatrical play. Givati never showed up for faculty meetings, which he found wholly loathsome, and at the end of the year, when the Department planned a general exhibition of all the students, he decided that his students had nothing to show. He believed that the exhibition only served the competition between teachers, and did not want to have any part in it. He gave all the students high grades, claiming that they all worked well throughout the year. His conflicts with the management gradually increased, until his work in the University was terminated.

Goldman Gallery became a type of Tel Aviv extension in Haifa. Following the 10+ exhibition “Venus,” Goldman held solo exhibitions for many of the leading artists of the time. Givati himself staged a solo exhibition in the Gallery which opened in May 1972. Comprised of oil paintings, screenprints and works in mixed media, it introduced yet another development of his ideas from his involvement in the quarry project, and touched upon ecological and technological contents. Critic Zvi Raphaeli summed the exhibition up as follows:

In large-scale canvases the artist reflects the conflict between wilderness and destruction on the one hand, and the reconstruction and rectification of that landscape, on the other. The graphic motifs that appeared in his previous works were diminished, and they now serve as a mere infrastructure from which neutral color elements bifurcate, intended to break the ostensibly functional ‘geometry.’ The geometrical hatching, symmetrical surfaces demarcated with an outline – a horizontal and vertical line – make room for sharp, poetical coloration. Furthermore, the artist has managed to lend the chemical material what it lacks; thus, for example, several oil paintings resemble fine watercolors, and even the ‘non-color’ is reflected as a colorist work par excellence. This time it seems as though the artist has freed himself from the Americanization that had often dominated his elements. Motifs of the immediate landscape are slowly created here. The color texture, rigid in the not-so-distant past, has become more subtle and sensitive. The architectural structure of the work is no longer as closed as it had been, but freer and more spatial. In particular, Givati has managed to introduce via mixed media, a dialectical dialogue between quasi-Fauvist spontaneity and concrete design (Haaretz, 12 May 1972 [Hebrew]).

In September 1973 the exhibition “Graphic Art in Israel Today” opened at the Helena Rubinstein Pavilion. This prize awarding exhibition was initiated for the State of Israel’s 25th Anniversary celebrations. The 120 works by the 73 artists selected for the show, presented a wide range of print techniques: woodcut, various types of etching and engraving, screenprint, and mixed techniques. Givati presented two screenprints which awarded him the second prize of 1,500 Lira. The prints were extracted from a series of landscapes in which he incorporated graphic elements that reinforced spatial and fragmentary effects of an arid lunar landscape alongside a blossoming of earthly nature in blue, green, white and black, at times combined with touches of another color, or alternatively, reducing the coloration to two hues only. Haim Gamzu sent Givati his congratulations for the award.

Body Imprints: 1974

Art lover and collector Freddy Kwiat purchased two paintings by Givati following his exhibition at Mabat Gallery. He continued to follow Givati’s activity, and asked Ephraim Ben Yakir for the artist’s Tel Aviv address. Later on he also came to Haifa, purchased all the paintings from Givati that were available in his studio at the time, loaded them on a small truck he rented on the spot, and drove off. When Dvora Schocken opened her gallery at 59 Hovevei Zion Street in Tel Aviv, Itche Mambush brought her and her husband Gideon, to Givati’s studio where only several rolls intended to be destroyed remained. The Schockens already owned a small painting by Givati for several years, which they purchased in an auction immediately after the Six Day War. Yael Givati gave the painting to Ruth Dayan to be sold in a benefit conducted by Dan Ben Amotz in Moshe Dayan’s house, while her husband was staying abroad. When the two heard that all the paintings from the studio were in Kwiat’s possession, they went to his storehouse and purchased a large number of works from him.

Givati now had contacts with Goldman Gallery in Haifa and Dvora Schocken Gallery in Tel Aviv. The International Art Fair opened in Düsseldorf at that time, and Givati decided to go to Germany. In Düsseldorf he ran into Joseph Beuys who came to one of the exhibition venues in the city with a group of students dressed in strange costumes, and the entire incident deeply impressed Givati. From there he went to stay with an Israeli friend, a well-to-do contractor who lived in the middle of a forest near Frankfurt:

He had an entire zoo there, a private stream, and a habitat for trout. We went to Frankfurt. We drank vodka all night long in some bar. When I woke up in the morning with a terrible hangover, the German housekeeper told me that war had broken out in Israel. We turned on the television, and suddenly I recognized the son of a friend, standing with his hands raised above his head in Syrian captivity. This is how I found out that the Yom Kippur War broke out.

Moshe Givati imprinting a model’s body on canvas, Haifa, 1971

Givati stayed in Germany for only a week, and rushed back to Israel on the third day of war. For six months he served as a tank crew member in the northern Suez Canal, and only at the end of the war returned home, to intensive work in the studio. On April 1, 1974, his solo exhibition at Dvora Schocken Gallery opened. Givati presented mainly paintings of body stamps on large-scale canvases, alongside screenprints and paper works in various techniques. Imprinting of the models’ bodies was executed both as a performance in and of itself, documented in photographs, and as a basis for paintings, which he reworked with a brush. The authentic presence of the female body unfurled across large canvases on which he painted interpenetrating, multi-leveled structures and refractions which spawned a perspectival interplay. The exhibition, which was installation-like by nature, raised controversial views: Rachel Engel of Ma’ariv regarded the body of works favorably, perceiving it as an integral part of Givati’s engagement in the art and print techniques in which he had trained in Paris and in his Haifa workshop:

Moshe Givati, one of the most conspicuous among the younger Israeli painters, has recently opened a new solo exhibition (at Dvora Schocken Gallery), where he presents mainly large-scale canvases created in the past three years, distinguished by a unique character… His beautiful screenprints, occasionally shown in group exhibitions, have already attracted public attention. In his current exhibition, Givati presents ‘prints’ of a different kind. In fact, these are oil paintings executed with brush in a distinctive painterly technique, layer upon layer upon layer, but the point of departure for the painting is a stain not rendered with a brush, but rather ‘printed’ on the canvas with the body of a woman who served as a model. Givati colors the woman’s nude body in oils, and then rolls her on the canvas extended on the floor, until the impression of her body is printed on it. Around it the artist constructs his composition – dulled-soft, quasi-abstract figures alongside sharp-contoured, rectangular and rigid forms. The final result – the painting – is a large picture whose theme is definitely man and landscape. For instance, one such large canvas – a ‘living-fleshy’ nude section within a natural setting and cityscapes. The colors – it is time to talk about them – are the light, ostensibly-faded hues of azure, light green, pink and purple, all of them, in fact, sky-colors, if one may use such a term, as opposed to the worldly, heavy-brown ‘earth colors.’ The ‘body print’ infuses the canvas with a dynamic of sorts, vivid-warm movement, a type of occurrence, unrest. In Painting no. 6 the body print is repeated several times, and its setting is all dulled by the layers of white paint which Givati applies to the depicted subject time and again, painting and covering, and so on and so forth. Bodies upon bodies shed their forms, transforming into white shadows of themselves, incarnating in various forms (Ma’ariv, 19 April 1974 [Hebrew]).

The Jerusalem Post published another favorable review, by critic Gil Goldfine, who shed light on yet another angle in these works when he identified allusions to romantic landscapes in the abstract paintings:

Moshe Givati’s recent paintings are epic and grandiosely handsome abstractions which vaguely suggest landscape. Large canvases, measured in meters, virtually hide the gallery walls. Upon entering the room the viewer is enchanted by billowing spaces that open before him, and with a bit of imagination, is engulfed as a participant rather than as an observer.

The pictures are smartly composed of components organized around a division of the surface into quasi-interior rectangular compartments. Within these frames the horizonless craters of infinite space are formed by transient patterns of active rhythmic movements created by Givatis lyrical style and impelling brushwork.

Concentrating on blues, Givati builds a rich spectrum ranging from lustful ultramarines and cobalts to delicate turquoise and cerulean. Although color limitation if prevalent, it is not the rule. Occasional bursts of secondary hues are in evidence, but Givati’s accepted norm of variegated colors is blatantly absent (but not missed) from these canvases.

A recurring theme is a headless female torso. Graphically stated and superimposed onto the surface rather than painted into the composition, it possesses the qualities of symbolic reality posed amidst the abstract swirls of pigment and illusionary space. On one hand the torso is a heavy-breasted fertility figure from pre-history, and then again she appears as a graceful classical marble, reminiscent of the Victory of Samothrace. The inclusion of a solidly painted slap protruding from the free flowing brushwork indicates some form of architectural structure and adds mystery, if not literal meaning, to the abstract fields.

Givati’s plunge into spacial and symbolic illusions has resulted in marvelous canvases of a sprawling romantic nature. Despite their abstract base, the scale, dynamism and total concept curiously parallel the grand tradition of Italian interior decorative painting epitomized by masters like Correggio, Tintoretto and Veronese. Whatever his ultimate objectives may be, Givati has taken the right step by cultivating a change from bold and pragmatic delineation to a more mellow and intuitive style (The Jerusalem Post, 12 April 1974). Another view regarding Givati’s treatment of the human body was offered by Nitza Flexer in Davar:

Givati created adaptations of the formal options and dynamic postures of the human body. Attempts had already been made at realizing conceptual ideas and articulating an existential view by painting the human body several years ago; Givati continues this line, by using the body as a source of inspiration for projection of amorphous color stains that fuse to form figures in various poses. The figures unite with the backgrounds, and the surfaces break with the introduction of anomalous levels that hint at a change in perspective.

The artist’s treatment of the human body calls to mind the approach of Italian Renaissance artists to weight and the emphasis to volumes, generating a strict style. Givati uses the heavy style without the volumes, neutralizing the figures of any similarity to a personal portrait. His monumental figures are somewhat reminiscent of the presence produced by Michelangelo from his human depiction. Light and shade disappear, and are replaced by factures and color tones (Davar, 24 April 1974 [Hebrew]).

Varda Chechik wrote in Al Hamishmar:

The paintings presented in the current exhibition are fine looking; they contain a subtle sensuality, and the exhibition gives the viewer great pleasure. Something in the contact between color and canvas surrenders a different painting mode. Approaching the canvas, one may discern the textures of paints in traces of rubber shoeprints, and in the naked body – in the impressions of the skin, with its various orifices and signs. On further viewing from a distance, the beholder feels a sense of conclusiveness-inconclusiveness, a certain tremor that the artist has managed to bring into the canvas (Al Hamishmar, 10 April 1974 [Hebrew]).

The same article also includes an interview with Givati, where he explains the work process on the series of body imprints:

I stretch a large canvas on the floor, and initially construct the color texture of the work with the models (two of them). At this point I am still not particularly interested in the body shapes. In the second phase I emphasize loci of my choice. At times, when I want to obtain a different contact with the canvas than the quivering touch of the body, I wrap one of the models in a material such as polyethylene, thus generating artificial, synthetic sub-forms within the forms of the naked body. At times I subsequently process the canvas laboriously, and then the initial forms burst forth. Sometimes there is a phase in the finished work where the viewer can discern both the work process and the finished result (Ibid).

But the canvases that were characterized by airy, fluttering touches and distinctive aquarelle qualities did not find favor with all the critics. Sarah Breitberg’s article, “External Mannerism or Real Necessity?”, indicated a different view from that of her aforementioned colleagues with regard to the works’ implications and reflections:

When I think of quintessential lyrical-abstract painting, Stematsky and not Zaritsky, considered the forefather of this current, comes to mind. Stematsky’s work is wholly a quest for the unclear, whose touch is truly hesitant and whose painting (for this type of painting intends to document and expose the painter’s inner self) attests to his being an introverted figure trying to hide itself even on canvas.

Givati, at least formally, belongs to this current. The color application and choice make him stylistically a young follower, even an innovator of this school. But here I go back to start – because in Givati’s work the Lyrical Abstract appears like external mannerism rather than a real necessity that truly reflects a state of mind and a worldview. Lyrical Abstract, like the more aggressive Abstract Expressionism, requires high involvement of the artist in his work. The entire painterly process in such work is like a seismograph that conveys the artist’s character and feelings via the brush strokes, their intensity, and the colors of the painting. Since we are concerned with an entirely abstract painting, the artist does not have a theme to cling to in order to cover himself, and he paints mental self-portraits.

It is hard to determine why Givati’s refined painting seemed to me as though it uses this technique outwardly. I don’t know the artist, and even if I had, I would not have purported to analyze his character and compare it to what is reflected in his paintings. Nevertheless I would like to argue, based on this painting alone, that his work as a whole appears too elegant, too calculated and too intentionally refined to be perceived as genuine.

I was told that in the current exhibition Givati’s painterly point of departure was ‘live imprints’ on canvas. Givati colored a nude woman, pressed her body onto the canvas when the paint was still wet, thus obtaining a live print of a female nude (indeed, this is not an original idea). Thenceforth, he started processing the canvas, where the print of the nude body served as a realistic reference point around and on which he developed the abstract. The finished work is so processed, that it is hard to tell it originated in a real, live print of a naked woman. The viewer thus misses the interplay between real and imaginary, which could have been an interesting element of tension on the canvas (Yedioth Ahronoth, 26 April 1974 [Hebrew]).

Ran Shehori’s review in Haaretz was even harsher. He negated forthwith the idea of stamping the canvas with the naked body, regarding it as an absurd, imitative phenomenon. In his review he emphasized that Givati:

...repeats Yves Klein’s method, who smeared models with paint and let them rub against the white canvas. What was, in Klein’s case in the early 1950s, the beginning of daring, innovative artistic thought and a search for meaningful expression that largely paved the path to neo-figuration and ‘Pop’ – becomes in Givati’s case a ‘gimmick.’ Stamping the naked body against the canvas undergoes a meticulous brush reworking, so that in the final result – large, airy, saccharine-sweet canvases replete with details – nothing is left of the initial process (Haaretz, 26 April 1974 [Hebrew]).

Moshe Givati in the northern Suez Canal,

1973-1974

In effect, however, Givati did not try to revive or imitate Klein’s method, but simply to use it for his needs. The significance of the body prints was manifested precisely at the point where the eye captured the loss of reality in the split second of the body’s fluttering touch on the large canvases, and in the stamped figure’s inclination not to be fixed on the body of the canvas, but rather expropriate it each moment anew. Consequently the feeling of a body simultaneously in a state of entry and exit was invoked. Despite the aesthetic observance of balanced composition, and the complementary “treatment” given to the female body, the imprint of the ostensibly-a-priori-erased body was but a part of an indefinite, dissolving space.

In the mid-1960s and early 1970s, before the Yom Kippur War, Israeli avant-garde artists engaged in environmental art and created conceptual-political works with a political-utopist air. In the wake of the war, however, the political artists were infused with a new spirit that made them even more radical. This tendency gradually evolved in the 1980s and 1990s, and continues to this day. The spirit of the 1970s, which bore the echoes of conceptual art, pushed painting aside. The pure aesthetic discussion of painting lost its relevance with the younger generation of art critics.

Givati himself continued to pursue painting and print techniques. Following the exhibition at Dvora Schocken Gallery, and after donating one of his body imprints series to the collection of the Tel Aviv Museum, Haim Gamzu invited Givati to present a solo exhibition at the Museum. In the contract signed between them it was agreed that the exhibition would be staged at the Helena Rubinstein Pavilion on October 15, 1975. Immediately after signing the contract Givati left for New York, mainly to rest from a long and tiring reserve service. Yael and the children stayed in Israel. Two of them were already serving in the IDF.

|