| Hana Kofler

Paris: 1966-1968

Givati’s involvement in the 10+ group was cut short in 1966, due to a trip to Paris, and was resumed only several years later, toward the end of the group’s activity, when he returned from his world travels. Givati’s declaration that he intended to leave the country again caused a conflict with the kibbutz members who did not regard his frequent travels for unlimited periods favorably, but he refused to succumb to the pressure and flew off:

For some time I lived in Hanna Ben Dov’s studio at La Riche. I slept in the upstairs balcony, and in the morning I would evacuate the place to let her paint. Close to La Riche there was a big slaughterhouse, with a family restaurant, where I ate for next to nothing, like all the other artists.

Untitled, 1967, mixed media on paper,

32 x 28, collection of Ora and Benjamin

Segalis, Caesarea

Givati looked for paying work to cover his stay in Paris. At La Coupole he met singer Bracha Zefira, who introduced him to Yaacov Agam. Agam’s studio was like a small factory for kinetic art, and he offered Givati a job on the spot. After a week Agam asked Givati what he thought about the works he helped create in his studio:

I told him that the work was very aesthetic, but beyond that I knew nothing about kinetic art. I explained that I was a brush artist. He forthwith sent me home to paint, and told me to come back every Friday to collect my pay. In effect, he paid me to sit at home and paint, and never asked for a return. Later he purchased a fancy apartment in some building occupied exclusively by the French elite, and held a housewarming, to which he invited all the French art community and various men of means. There were Meshulam Riklis, Yona Fischer, Pierre Restany, and, of course, many of the Israeli artists – some long residents of Paris, and others who had newly arrived. That day he sent a driver to my place and asked me to load the car with my paintings. I arrived at the party with Hanna Ben Dov. Agam asked all the artists to bring catalogues and photographs of their work with them. The goal was to try to sell paintings to Meshulam Riklis. At some point Agam led Riklis to the room where my paintings were hanging.

Untitled, 1967, watercolor and Indian ink on paper, 16 x 24,

collection of Noa Tarshish, Haifa

The next day, on Saturday, I sat at Café Select on my way to the opening of the ‘May Salon’ dedicated to kinetic art, where Agam exhibited some large-scale works. The first to come rushing toward me was Yehuda Neiman, who congratulated me that Riklis had purchased all of my paintings. Kahana, who arrived after him, congratulated me as well. This is how I found out that all my paintings were sold. When I arrived at the ‘May Salon’, Agam approached me and told me that Meshulam bought only four paintings, but that he spread the word that all the paintings were sold. Forthwith he asked me not to reveal the truth, and unfolded his theory about the right conduct to make an artist successful. He gave me a quick lecture about the value of artist jealousy and the way to create a prestigious image. Riklis paid me generously, a sum of money that covered the rest of my stay in Paris. Years later I met Riklis’s ex-wife at a Chanukah party held in the house of Meir Levin, a New York print publisher, and she told me that two of my paintings were at that very time making their way to Israel in a container, and the remaining two remained with Meshulam. In their divorce agreement they divided the paintings I had created and sold in Paris equally between them.

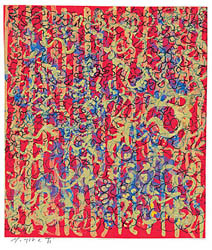

Textile design for the fashion industry,

Paris 1966, mixed media on paper,

19 x 15, collection of The Bar David

Museum, Kibbutz Baram

Several months later Givati returned to Israel, but immediately asked to leave for Paris again. The kibbutz secretary, Ezra Ben Dor, who was a teacher and an educator, asked Givati to persuade him that it was a crucial move before he agreed to urge the secretariat to approve his trip in their next meeting. “He succeeded, and my trip was approved,” says Givati, “he just recommended that I leave the kibbutz as soon as possible, because one of the members, who was absent from the meeting, had already filed an appeal.” Before leaving, Givati was asked to prepare the set for a play staged by the kibbutz members after a story by Nathan Shaham. He created décor on wheels which elicited great admiration among members.

On the eve of his next trip to Paris Givati met Chana Orloff, who came to Israel frequently during the 1960s for family visits and for the openings of her exhibitions and installation of her sculptures. Mr. Rabani, an art collector and Orloff’s close friend, who was also a friend of Pinchas Abramovic, introduced them. When Orloff came for a visit in Haifa, Rabani took her to Givati’s studio in Sha’ar Ha’amakim, where they also discussed Givati’s upcoming trip to Paris. Orloff, who was known for her special relations with the Israeli artists (who constantly streamed into the City of Lights, for short as well as long sojourns), set up another meeting with Givati at Café Dome, warning him not to be late. When Givati came to the meeting on time, Orloff was already waiting for him.

After arriving in Paris and renting a small studio apartment, Orloff came to visit him. She climbed three floors up the narrow staircase and purchased two of his small paintings (The paintings were presented in the exhibition “Private Collection: The School of Paris & Eretz-Israel Artists chez Chana Orloff,” Mané-Katz Museum, Haifa, 2002).

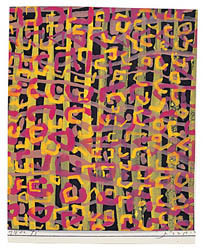

Textile design for the fashion industry,

Paris 1966, mixed media on paper,

20.5 x 18, collection of Eli Lancman,

Haifa

She told him that at the outset of her career in Paris she made a living in textile design, and advised him to paint several patterns on paper, although professional pattern-making is done on cardboard, since the latter required certain technical know-how. Givati took her advice and prepared a sample portfolio of textile paintings:

I walked down the Champs-Élysées with the green sample portfolio. It started raining. I found myself standing in the entrance of a famous fashion house, and walked in for shelter. The receptionist asked me in French something I didn’t understand, but ended with the words ‘textile design.’ I nodded, and she sent me upstairs. I climbed up and sat down. When the door opened, I was called in. The man who welcomed me spoke English. He liked the samples, noted the nonprofessional presentation, but nevertheless gave me a letter bearing their logo. He referred me to a company named Trikozan, where I met the owner, who was Italian. She picked ten patterns and paid me 4000 New Francs, which was a fortune to me. Before I left she mentioned that the samples should be made in a special technique.

I still lived in the same small flat, where I was even hosting Ury Lifshitz who had come for a visit from Israel. I was enrolled for art studies at the Beaux-Arts and turned up for lessons every now and then. There I met Kirsten, a Danish girl who was connected with the dance troupe of Francois and Dominique – rich kids who had a fancy large studio in Pigale. They were dancers and choreographers, and they invited me to prepare costumes and sets for their next performance. They staged the performance in Provence, and I joined them on the tour, for which they paid me generously. In the meantime, I was invited for dinner, together with Shlomo Cassos, by a well-to-do Jewish family that owned an empty spacious apartment. We befriended. Their daughter visited my family on the kibbutz, and they let me stay in their apartment, where I had my own shower – a real luxury in Paris at the time. At long last I had lots of room in which to live and paint.

Orloff invited me for dinners in her home at Villa Seurat. She was a great cook. She used to say she created and sold sculptures only so she could eat better. We would usually eat in her wonderful kitchen. On one occasion she prepared a meal in honor of Ardon, and invited me as well. In the middle of the meal she pointed at the wall and yelled at him (because she was hard of hearing): ‘You see the Modigliani there? Next to it there are two paintings by Givati.’ This was her special way of expressing her fondness; perhaps she just wanted to tease Ardon. Lan-Bar and Kahana were her best friends and they often visited her at home. Lan-Bar used to move from one café to the next. I often joined him. He was a good painter and an expert in bargain hunting. As for Kahana, I visited him in his studio often. He died in Paris shortly thereafter.

I left Paris hastily due to the Six Day War. When I was still waiting to return to Israel, I performed security duties with two other men: a young rabbi who lived outside Paris, and another fellow who was a vet and was later killed in the war. We were charged with guarding the El-Al planes at Orly Airport. The planes flew back and forth, and led trucks of sorts.

At some point I decided to go back to Israel. I bought a ticket and boarded an Alitalia plane. My family waited for me at the airport. We drove for hours in a jeep whose headlights were turned off due to the blackout. When we arrived in the kibbutz early in the morning, the outbreak of the war had already been announced on the news. I packed a bag and hitchhiked north, to my IDF unit, which was already in the orchards of Kibbutz Gadot. I wasn’t in the first wave that went up to the Golan Heights. When we got there, we encountered many bodies of Syrian soldiers. When I returned to the kibbutz, I found out that my shack had virtually collapsed. People went in, and each one took a painting. For the time being, they let me paint in a henhouse which was slightly fixed up for that purpose, but then it was needed, and they offered me a residential apartment – a highly unusual offer in the kibbutz at the time. That apartment was a wonderful studio. They even talked about the possibility of building a special studio for me, and I was treated exceptionally well. In the meantime, a friend from Paris removed my belongings and returned the apartment where I had stayed to its owners. I loved Paris and enjoyed every minute there; I thought I was going to return there, but when I came to Israel my plans changed. Hanna Ben Dov removed the canvases from the frames, rolled them up and stored all my paintings in her studio. They lay there for years, until Charles Tapiero, an art collector, brought them from Paris. It happened when I already worked in my studio on Neve Sha’anan Street. I handed the roll, which I carefully preserved, to Haim the frame-maker, and he stretched all the paintings anew. I wanted to keep them in one group and not to scatter them, but since I made my living exclusively from painting, I eventually sold them to anyone who was interested, and they were scattered among collectors and art lovers.

Untitled, 1964, oil on canvas, 20.4 x 20.4,

estate of Chana Orloff, Paris

Untitled, 1964, oil on canvas, 35 x 33,

estate of Chana Orloff, Paris

New Beginnings: 1968-1970

During 1968 Givati had a solo exhibition at Goldman Gallery, Haifa, where he presented large-scale canvases again. Miriam Tal concluded the review of his exhibition thus:

A talented painter who combines a refined use of a light gamut, formal spurts, violent, even raw coloration, and transparent geometrical elements in his large-scale canvases; his recent paintings also contain found elements, such as enlarged photographs of skulls, relevant figures. The mental climate is violent. At times even erotic… The paintings where the visual and physical presence of death is felt are convincing in their frankness (Gazith 26: 1-8, 1969-1970 [Hebrew]).

Yona Fischer arrived for a visit in Givati’s studio on the kibbutz with Ephraim Ben Yakir. Ben Yakir had just opened the Mabat Gallery at the time, and was looking for artists to exhibit there. Tumarkin had just left Gordon Gallery and moved to Mabat. Givati signed a contract with Ben Yakir, which included a large industrial space at 34 Yitzhak Sadeh Street, and started painting intensively. Despite the good conditions he was offered by the kibbutz, he preferred the Tel Aviv option and the possibilities it opened up for him. His family stayed on the kibbutz until the end of the school year, and he used to visit them on weekends, and dedicated the rest of his time to work. The only person who came to visit him in his studio in those days was Joav BarEl (whom Givati met once when he came with his Susita Sport to lecture at Sha’ar Ha’amakim). They once went together to Ha’teatron Club. Joav didn’t drink, and therefore they didn’t hang out together in places where the bohemian drinkers used to sit. Tumarkin came for a single visit in the Studio on Yitzhak Sadeh Street. “It was a very exciting time for me,” Givati recalls. “Whenever I finished a painting (and I worked a lot), I would carry it to Mabat and hang it on the wall right away. Tumarkin used to tease me for this.”. The dissociation from his family and the distance between Tel Aviv and Sha’ar Ha’amakim, however, made Givati’s life difficult, and he and Yael decided to leave the kibbutz:

On one of my visits to the artist village of Ein Hod with Ephraim Ben Yakir and a hangover, we met Itche Mambush, who told me that Henry Shelesnyak’s house was for rent. I returned to Tel Aviv, and signed a contract with Henry for six months. We enrolled the kids in the regional school, but there were very few children in Ein Hod, and we felt that the choice of place was a mistake. We didn’t like Ein Hod for many reasons. I went to Haifa, and with the help of a real-estate agent, I found a large, spacious apartment on Shoshanat Hacarmel Street. We moved the children to a nearby school and settled in Haifa.

1969 was an especially fruitful year for Givati, in which he staged three solo exhibitions, in Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, and Haifa. In April, he opened a solo exhibition at Mabat Gallery. Tumarkin came to visit, wrote encouraging words on a note, and wished him luck. The critics were kind as well. Ran Shechori wrote about the exhibition in Haaretz:

Four different painterly approaches merge in Givati’s recent works: 1) low-tension lyrical coloration based on free application of closely-hued blots of color; 2) contrasted expressive coloration achieved via swift, nervous brush strokes and exhaustion of sharp color tensions such as black-red; 3) geometric elements and smooth, sparse color surfaces borrowed from the Geometric Abstract; 4) print and figurative elements, such as photographs or paintings, in a technique akin to Pop.

In the past Givati deliberated between these various approaches and tried to combine geometrical elements in his essentially lyrical painting, which usually dissolved under his hand and lost their power, even causing a blurring of the lyrical values. In his recent works he seems to have found the way to obtain such combination: the center of the painting usually tends toward erupting expressivity, generated due to the sharp color tension, the crude factures, and the fast, nervous brush rhythms. This pungent lump is balanced and restrained via broad geometrical surfaces, some colored coldly and rigidly with thick paint that cuts the amorphous forms at the center, others with a quiet, diluted coloration in myriad fine middle tones. This conflict spawns a canvas richer in color and visual occurrences. Givati manages to preserve the spontaneous freshness of the canvas, and at the same time, sustain a calculated, careful balance between the different elements. The three last works (nos. 4, 5, and 9) attest to yet another direction; these canvases tend toward a more rigid geometrical style and stricter color restraint. They are constructed as clean surfaces of color cut by figurative elements, such as skulls or nudes. There is an interesting tension here between sharp color contrasts and painterly nuances, such as pencil scribbles revealed under the translucent layers of paint, or light drawing (Haaretz, 2 May 1969 [Hebrew]).

Shechori’s review unfolds the many transformations and innovations that Givati’s work revealed at the time, although in retrospect, one may say that these changes were a part of the jolting ritual that has accompanied Givati’s practice throughout the years. For many years his work underwent changes reflecting his deliberating, influenced, kicking, constantly searching personality. His paintings from that period are indeed typified by an uncontrolled outburst of creativity, but closer examination of his works, from this and other periods, also reveals other facets in his artistic persona. Perusal of his artistic path shows an artist almost constantly immersed in deliberation that manifests itself in his great difficulty to express what sizzled within him throughout all the phases of his confrontation with the canvas.

Reuven Berman was likewise impressed by Givati’s exhibition at Mabat, and compared his new works to those he had exhibited at the 1968 Autumn Exhibition. In his review Berman indicates the fundamental change in Givati’s approach, noting the spontaneous painterly qualities and the disappearance of the rigid line from his works:

But not only slashing turbulent brushwork, savagely distorted figures and carcasses and an undercurrent of violence mark these large canvases – there is also that special blending of images, descriptive and abstract, fleshy and free-handedly geometric, special to Israeli surrealistic-expressionism and its unknowing godfathers Rauschenberg and Bacon. These new paintings also reveal a conscious effort to destroy the impression of ‘refinement’ characteristic of all Givati’s works until now, and to snarl with compulsive aesthetics-be-damned emotion (The Jerusalem Post, 2 May 1969).

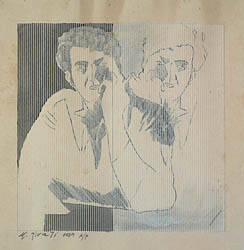

Self-Portrait, 1969, pencil on screenprint,

22.5 x 24, collection of Eli Lancman, Haifa

Berman identified the influences of Tumarkin, Lifshitz, Lavie, and Shelesnyak in Givati’s new works, and noted the keen sense for composition with which he was endowed, the gift for extemporaneous invention, and his feel for the versatility of paint. These qualities, Berman concluded his review, come together to produce paintings of great vigor and perfection.

When the exhibition closed, Givati canceled his contract with Mabat Gallery, but two years later returned to exhibit there.

In October 1969 Givati was invited to exhibit at the Jerusalem Artists’ House together with his colleague, Henry Shelesnyak. The two shared a single exhibition space, where Givati settled for presentation of two paintings and two drawings. His canvases stood out in their division of space into sharp, clear-cut circles and squares, and the use of elements of painting, drawing, print, adhesion, handwriting, scribbling, and graphic effects. The coloration was light, and was dominated mainly by pink and gray which emerged from the canvases’ paleness. Especially impressive were the unusual space divisions on the canvas, and the sophisticated, accentuated delineation of the figures and their location on the painterly surface. Shelesnyak’s works were characterized by distinctive minimalism of color and form. They were dominated by white, which became a key element in his work and one of the challenges he had already faced earlier in the 1960s, even before he became acquainted with Rauschenberg’s work, as well as after he viewed his group of “white paintings” the year before in New York.

Lea Mejaro-Mintz wrote about the exhibition in Hayom:

The most conspicuous among the soon closing exhibitions at the Artists’ House is that of Moshe Givati. Stylistically, Givati belongs to the group of artists who have adopted a mode of expression combining geometrical forms with classical drawing – a blend that has moved forward in the world in recent years. This style combines a lucid, rational approach, and clear drawing on the one hand, with well-defined geometric forms on the other – a reaction of sorts to the emotional-spontaneous approach of Lyrical Abstract. At the same time, this style introduces the viewer to a labyrinth of situations, juxtaposing excerpts of ideas. Within this style Givati manages to display superb technical quality in clear, accurate drawing, as well as a refined sensitivity to color. In addition, he succeeds in incorporating multiple strata and forms that come together to create a syntax invoking an emotional experience where the vague and lucid are intertwined (Davar, 17 October 1969 [Hebrew]).

With regard to the drawing, however, some critics disagreed with Magero-Mintz. Naomi Benzur wrote that the works display “an all-too-hesitant drawing,” and that “the combination of elements characteristic of Givati often generates an overflowing work.” (Ma’ariv, 24 October 1969 [Hebrew]). Ran Shechori maintained that “despite the multiplicity of elements, the painting retains its color transparency and formal clarity due to the rational area division and fine execution.” (Haaretz, 10 October 1969 [Hebrew]). In any event, the diversity of opinions voiced by the critics with regard to Givati’s work indicates lively attention to his work in the local art milieu of the late 1960s.

Still in December of that year Givati opened a solo exhibition at Goldman Gallery, Haifa, where he presented relatively small oil paintings in which he repeatedly attempted to redefine the human figure. In reference to that exhibition, Eve Goldman wrote:

Givati’s man is an other… On the whole, his work is dominated by a reduced process in all categories of painting: he usually settles for various pinks and whites, thin processing of broad color surfaces, and implied sculpturality of his figures (Ma’ariv, 19 December 1969 [Hebrew]).

Zvi Raphaeli articulated a different impression:

The exhibition’s theme is drawn from a world of quasi ‘cultural’ substitutes, from the rosy, sweet world of the man-on-the-street. Men’s heads grow decorative flowers of sorts, reminiscent of caricatural horns, speckled robots rendered in confetti-like dots, carried atop a geometrical construction. Showcases ‘for all to see’ and small boxes of sterile rooms become cosmetic commercial alcoves or erotic cubes of contemporary ‘progress’ (paradoxically, a type of vulgar, loathsome, disgusting rococo is created here). Despite some external influences, from American Pop (Allen Jones), there is more of an unconscious adaptation and subconscious assimilation here, rather than pure imitation; the artistic motivation and the meticulous architectural design of the painting differ from the works of most of the artists in the gloomy Israeli Autumn Exhibitions (Haaretz, 12 December 1969 [Hebrew]).

Indeed, Givati’s paintings from that period were governed by minimalism of form and color, on the one hand, alongside outbursts of warm, sharp color and aggressive drawing, on the other. Black emerged on the canvases in different variations, becoming gradually more dominant and lending the painting a calculated composition and a dark, mysterious air.

10+, Last Shows: 1968-1970

Givati did not take part in the next exhibition of 10+ held in December 1968 at 220 Gallery under the title “For and Against,” since he was busy reorganizing his life. The artists in that exhibition were asked to respond to their social and cultural environment. The participants included poet David Avidan (who was For Against and Against For), playwright Hanoch Levine, who co-exhibited with Michael Druks (Man and Wolf ), Avraham Eilat (who presented transparent plastic boxes filled with “chunks of meat” that threatened to spill out), Raffi Lavie (who presented the work Post Mortem), as well as Yaacov Dorchin, Yair Garbuz, Henry Shelesnyak, Alima, Aviva Uri, and others. Of the “ten” who founded the original group, only Lavie participated in the exhibition.

Three months after the 1969 solo exhibition, Givati once again joined the members of 10+ in the group exhibition “Circle” that opened in August of that year at Gordon Gallery. For his work in the exhibition, he used screenprint on Japanese canvas mounted on circle-shaped plywood on which he painted a “leaf” in acrylic. From this essentially airy work the shades of pink and azure emanate, bursting out between the dark area and the white part, creating a fusion between a duplicated human figure and an unidentifiable, yet intriguing landscape.

Yigal Zalmona summed up the exhibition retrospectively in the culture and art review Musag:

Generally it seemed that the artists had already become accustomed to the type of challenges introduced by 10+, and learnt to fully exhaust the theme, to employ unusual techniques and materials, and to strive for the unconventional (Musag, 6 November 1975 [Hebrew]).

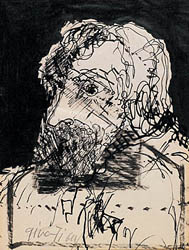

Self-Portrait, 1969, Indian ink

on paper, 20 x 16, collection of

the Kwiat Family, Givatayim

Twenty-six artists participated in that exhibition. Mina Sisselman who reviewed the summer exhibitions, wrote that in the group’s previous show the participants arrived at more interesting results, such as in the exhibition dominated by the red stain (Sisselman herself participated in the “Exhibition in Red”).

For many of them this is a first exhibition, and one is impressed that the challenge is beyond their capacity. Most of the participants referred to the circle as a square, and those paintings executed within a circle could be squeezed into squares without feeling any real difference. Most of these artists presented compositions of ordinary painting based on transparent layers of paint, or line scribbling, and pressed it into a pure geometrical circle - two antithetical elements

In her essay in Hayom, Miriam Tal lingered on each of the participating artists from a generally favorable position toward the exhibition, blended with little criticism:

As in the other exhibitions of this group, it contains interesting experiments and a fresh, pungent, impertinent spirit; there is a quest for ‘clean’ forms without sentimental baggage; but there is also a profusion of absurd, or simply entertaining, phenomena. One senses a tendency among several artists to evolve toward relief sculpture or kinetic art (Hayom, 1 August 1969 [Hebrew]).

Tal goes on to commend her favorite works, especially Batya Apollo’s, criticizing what she perceives as “the result of chasing ‘avant-garde’ that has long been dressed in shrouds, in both Paris and New York,” words which she deemed most appropriate to describe the work of her colleague from the competing paper, Haaretz – Ran Shechori. To Givati she allotted a simple description that avoided taking a stand: “Moshe Givati turned to a synthesis of photographs (transferred to the canvas) in different variations, and painting that connects them.”

In that same year Raffi Lavie gave an interview to the Tel Aviv newspaper, and tried to explain to the interviewer, Liora Keren, what 10+ was, one minute before the group dissolved. To Keren’s question, why the group was going to dissolve only shortly after it was founded, Lavie replied:

The problems have been resolved, and the arguments and the democracy. Our intentions were good, but it simply didn’t work. Each artist wanted, for instance, to hang his work in the best space on the wall. […] The group was a total democracy. The codex says that everything must be unanimous. But ten horses pull the wheels in ten directions. There were, for example, those who perceived the group only as a means to exhibit, and were not at all interested in the themes. As for inviting guests, there were endless arguments about that. Time ran its course, and I think eleven of the ten went abroad Tel Aviv, 29 August 1969 [Hebrew]).

Lavie goes on to note that of the ten founding members of the group, only he and Pinchas Eshet remained in Israel. To the question what happened to 10+ after everyone went overseas, Lavie replied:

I stayed in Israel (I have never been abroad), and I felt sorry for the whole business. I decided to continue as sole initiator and setter. A dictator. My only crime was that I kept the name 10+. It was a good name. It was worth using to get to the audience. I was later joined by Joav BarEl and Ran Shechori, and the three of us now determine 10+ unanimously. With them I arrived at compromises and concessions. And we call ourselves impresarios. Now no one decides except the three of us. All the others are invited once a month. There is no option.

The exhibition “10+ on Venus” was held in May 1970 at Gordon Gallery. In the same interview with the Tel Aviv newspaper Lavie unfolded his thoughts about Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus, and its selection as the leading image for the ninth exhibition of 10+:

It triggers all kinds of associations. There is a star by that name, but this is beside the point. You just take Venus and create variations on it. The theme is difficult and intricate. We want to work on the theme together. Once again, only seven artists. We will meet, talk, exhaust the problems. The goal is to introduce a very clear theme through various perceptions, because it will not be allowed to change Venus. You will introduce Venus into your style, but it must be Venus, it must be recognized.

Ultimately, despite Lavie’s declaration that the exhibition will include only seven artists, 17 artists took part in it: Avital Geva, Yair Garbuz, Oded Feingersh, Panasi, Michael Druks, Batya Apollo, Aviva Uri, Raffi Lavie, Jocheved Veinfeld, Henry Shelesnyak, Avraham Eilat, Ziva Ron, Micha Lubliner, Ran Shechori, Michael Eisemann, Moshe Givati, and Igael Tumarkin. Givati was not invited to participate in the exhibition originally, but he prepared a work, which he brought to the gallery toward the exhibition’s mounting, and the painting was included despite Lavie’s protest.

In his critical review, Azriel Kaufman divided the participants into four groups:

The first – including Ran Shechori, Henry Shelesnyak, Moshe Givati, and Yair Garbuz – confronts a profound, in-depth search. Their works attest to realization of aesthetic values while creating a balance between material elements and conceptual-intellectual elements. The intellectual alertness leaves its impression on most of the paintings, saving them from falling into superficiality and amateurish experimentation (Haaretz, 22 May 1970 [Hebrew]).

The exhibition, as a whole, invoked antithetical views, but almost all the critics noted the small number of artists who hit the mark of their personal taste and provided some justification for the underlying theme. Reuven Berman, for example, was only impressed by the work of two of the participants:

The works of Michael Eisemann and Michael Druks carry most of the burden of bolstering up the anti-conventional ideal and/or reputation of 10+ (Yedioth Ahronoth, 22 May 1970 [Hebrew]).

Among the critics who wrote favorably about the works of Batya Apollo and Tumarkin, were also those who commended the pieces by Raffi Lavie and Oded Feingersh.

Givati’s Venus concluded the series of paintings where he made minimal use of color and drawing, as well as a smooth, calculated measure of area division on the canvas. Venus herself was depicted in this work via fine drawing that emerged from a geometrical composition. An amorphous stain in dominant pink stood out on the canvas, within the azure and black applied in exemplary order behind, and the demarcation of the square in pale (peach-pinkish) skin color in which Venus’s head was placed deepened the perspectival layer of the painting, lending it an additional dimension. As the square continued, Venus’s body led into the black strip that closed the canvas downward.

The “Mattress Exhibition,” which later turned out to be the finishing stroke of 10+, was held at Dugit Gallery in September 1970. The organizers planned to cover the gallery’s floor and walls with mattresses wrapped in uniform fabric in order to create a general sense of softness in the space. The result, however, was disappointing, and the critics regarded the exhibition, at best, as a tasteless joke. Some regretted the missed opportunity to present worthy environmental art for the first time, but the general atmosphere regarded the mattresses scattered on the gallery’s floor and walls, prodding the visitors to lie down, with amusement.

Raffi Lavie decided that 10+ had reached its end and exhausted itself. New galleries emerged which displayed openness toward innovative artistic phenomena, and the group’s members started to establish their place in the art milieu and did not require organizations such as those of 10+. The hostile reviews of the group’s two final exhibitions also helped put an end to its continued activity. As aforesaid, from the perspective of time, Yigal Zalmona maintained that 10+ “indeed buried Lyrical Abstract… because its members aligned themselves with global trends, yet it succeeded in introducing a value system radically alternative to the prevalent one.” (Musag, 6, November 1975 [Hebrew]). At the same time, one should bear in mind that the group members never declared such ambitions. Ultimately, their contribution to the politics and sociology of art was considerable, and to a large extent they shaped the evolution of the local art field since the 1970s. The group members turned their own ways, carrying considerable experience in staging thematic group exhibitions and with great openness to issues pertaining to artist-society-establishment relations.

|