| Hana Kofler

Exhibition at Dvir Gallery: 1984

In early 1984 Givati approached painter Shimon Avni offering to exhibit one of his works at Radius – an exhibition space that Israel Discount Bank allotted to artists in the Dizengoff Center mall, where exhibitions were held in the format of “colleague brings colleague.” Givati’s work consisted of four panels. Lea Nikel, who passed by, left him a complimentary note, flattering him for the large-scale work. The work was later purchased by the Migdal Insurance Company and partially damaged by some fault in the plumbing system in the company’s offices. Only two panels survived, and thus it was transformed from a polyptych to a diptych.

Dvir Intrator, owner of Dvir Gallery, came to see the exhibition, where he met Givati for the first time. Givati later called him and asked for his help in selling the painting because he needed the money. Following the conversation, Intrator came to Givati’s house to view other paintings, and a date was set for Givati’s next exhibition, this time at Dvir Gallery:

He asked whether I would make new paintings before the opening. At first I thought I wouldn’t. But then I remembered that I had a large roll of canvas in Nahariya. He arranged for it to be brought over. Yaacov Mishori stretched the canvases for me, and I started painting in an inexplicable furor. I painted until the last minute, and in the exhibition we hung still-wet canvases.

In June 1984 Ruti Rubin (Direktor) published an article that reviewed Givati’s life and art upon his turning fifty. For that article she visited Givati’s home and Dvir Gallery, conducted lengthy conversations with the artist and the gallery owner, and published a two-page article in the weekend supplement of Hadashot. Under the pungent title “Fifty Years of Solitude,” the article set out to assemble the complicated jigsaw-puzzle of Givati’s life, and understand how at fifty he still continued to kick in all directions:

‘Bad painting’ prevailed, and the audience, as usual, was thirsty for innovations.

Givati’s good painting, really good painting, fell in the cracks – it is too good, too high quality for commercial galleries or home exhibitions in Ramat Hasharon, and not ‘bad’ enough for Tel Aviv avant-garde abreast of the times.

Givati was a good example for the history of painting, but in the current-artistic pressure cooker he had no chance. The favorable reviews were a bear hug – suffocating, blocking, and lamenting one who in fact hasn’t even started. The artistic community in Israel expects that at fifty an artist will have characteristics identifiable from a distance – such as Raffi Lavie’s scribbles or Gershuni’s screaming inscriptions.

Deep within him Givati knows that he hasn’t started yet, that he hasn’t delivered his message, and this was the hardest thing of all. The truth was biting, the alcohol and solitude threatened to paralyze him. A fifty year old artist, who belongs to no clique, graduate of no school… Months have passed until suddenly, in one of the last exhibitions of the late Radius Gallery, a new painting was noticed, a painting by Givati, which made more than the usual number of people stop in front of it: four attached canvases that together formed a monumental abstract landscape, very green with red-pink stains bursting forth from below. It possessed more than mere professionalism and virtuoso mastery of color. Standing close to it, one felt enwrapped by the green. Anyone who saw the painting from up close said that something continues to burn in Givati (Hadashot, 29 June 1984 [Hebrew]).

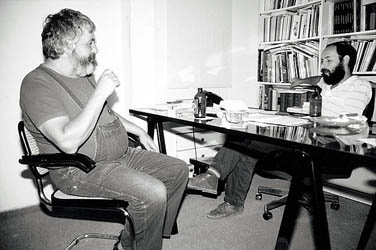

Dvir Intrator and Givati at Dvir Gallery, Gordon Street, Tel Aviv, 1984

Throughout the article Rubin (Direktor) attempts to “take snapshots” of Givati’s life, to describe entire biographical scenes that seem as though they were drawn from “a film that the God of Painting makes in the heavens about painters who struggle on earth.” She focuses on the painter staring at the blank canvas before him, on the empty cans of beer scattered all around, on the creative outburst that invents new images emerging from canvases saturated with color:

Givati paints new canvases, less lyrical, more defined, stronger. Something has happened to his painting. Something new has come out of him onto the canvas. He was alone in those moments, great moments in the life of any artist. What does one do with the new canvases? Paintings need an audience, otherwise they die in the studio, placed back to back by the wall.

It was probably late afternoon when Givati called Dvir Gallery. His life story, in addition to the gallery situation in Tel Aviv and the dynamics of artist-gallery relations, weighed down on Givati’s hand, the same hand that picked up the phone and called Dvir Gallery.

A white gallery with minimalist décor, in the middle of Gordon Street, Tel Aviv; a small shrine of contemporary Israeli art. Prestige, straight tall walls, what is called in gallery-talk ‘a good space.’

On the other side of the line Dvir, the owner, recalled the green painting, from Radius. Something told him at the time that the green painting would not be Givati’s last word. He was right.

Two people traveling in the same circles for years, saying hello, familiar with each other’s biographies, examining each other with suspicion, appreciation, curiosity. One sits in a white gallery with a good space, the other – no longer a young painter, operating near the margins of the art world, sharpening arrows of bitterness and despair, hiding behind the appearance of an aggressive, growling bear. Inside he conceals a big, vulnerable, easily-offended child.

It took a miracle, not a big one, but a miracle nonetheless, for something to happen here. Dvir stood before the new paintings and saw the spark. He saw new paintings and knew that he wanted to exhibit them.

Shall we make an exhibition? – he asked – perhaps in a month?

Givati said it was fine by him.

Only of the recent canvases…

Yes, that was fine by him too.

They selected seven new canvases, among them the green one from Radius.

‘Do you think, perhaps,’ Dvir asked cautiously, ‘you could try to paint another large canvas? To have something new for the exhibition…’

Givati was dumbfounded. He hadn’t yet digested the idea of an exhibition, and was already offered a new challenge.

Look – he hesitated – it is going to be a tough month, I’m going to be pressured, I don’t think I will be able to paint.

They agreed on the seven existing canvases. The invitations were printed and a date was set: June 24. This conversation, by the way, and what followed, is recounted by both Givati and Dvir separately, but identically. For both of them it was a click at first sight. For both, the exhibition was a sweeping, fascinating joint adventure.

In the meantime, Givati couldn’t resist the temptation, and thought perhaps he should, after all, try to create a new canvas. He connected two canvases he had at home, together 4x3 meters, and for four weeks, in seizures of work and drink, he created the best, most surprising and powerful four canvases he has ever created. He breeched the boundaries of abstract with figurative images that emerged from within color stains. He painted layer upon layer, each one better than its former. He worked long nights and drank whole days. He was in creative ecstasy.

At nights Dvir would come over, observe dumbstruck.

There were powerful blues and reds and oranges. Blurred figures, people and objects, hinted and swallowed back into the background.

In the morning Dvir would call Givati and tell him: This is the best thing you have created so far, but I think it is not the end of it, perhaps you should try some more (Ibid).

In his article, “Signs of Distress,” Ilan Nachshon referred to Givati’s attempt to take a big stride from the 1950s and 1960s to the 1980s:

From painting founded on touches, feelings, occupation of space, and qualities of color – to painting channeled into several images. It is a careful attempt by a seasoned professional, made with a confident hand, without losing his balance and personal identification.

Givati claims passionately that his sources of influence were the British Turner and American abstract which he encountered from up close during his sojourn in the USA… His new paintings ostensibly wish to affirm his own version of American abstract. His color melancholy has been replaced by an accentuated color gamut where red, blue, black, and purple are conspicuous, while the soft strokes were pushed aside by vigorous and highly expressive brush strokes. The canvases themselves have grown to ‘cinemascopic’ dimensions – 2 by 3 meters; various images protrude from them in a manner reminiscent of the new painting: sea, boat, a chair that loses its balance, figures, whale – that convey feelings of anxiety, escape, threat, distress, and loneliness.

Givati possesses the gift of formulation. Just as much as his paintings can be construed as personal-mental landscapes or a private nightmare, one can also assemble them into a political jigsaw puzzle hinting at current affairs (Yedioth Ahronoth, 29 June 1984 [Hebrew]).

Dorit Kedar discussed the duality underlying Givati’s new paintings in her article “Plastic Ambiguity”:

The artist positions the figures behind lines and stripes. These acquire a plastic ambiguity: on the one hand they indicate their superficial essence, and on the other – they emphasize the dimension of depth. The dualism is manifested in the canvases themselves. The works consist of two parts that together form a single grooved piece. Joyful, highly-nuanced, vital coloration is juxtaposed with deterring, expressive articulation. A distorted head whose features have been erased, oozes in all directions and downward, all the way to the vertical line from which it grows in a chaotic outburst.

Hanging left of the entrance are two works based on pure formalism. The ambiguous conflict occurs here as well: a combination of regular and irregular stripes, geometry and stains, but in the rest of the works there is the emotional factor that furnishes the whole with vitality, interest, and a desire to penetrate this strange beautiful world still further (Al Hamishmar, 5 July 1984 [Hebrew]).

Nissim Mevorach, who had previously commended Givati’s abstract painting, once again praised the non-thematic paintings in his article “Painting as a Narrative Text.” At the same time, the article indicates that Mevorach’s appreciation for Givati’s abstract strives to keep him in the fields of abstraction, and that figurative manifestations, however implied, cast doubts in him:

There is no sign of publicist contents that must be deciphered. He has gathered painterly statements in large quantities on extensive areas, whose fusion into one text is not discernible at first sight.

The exhibition consists of six works altogether. A certain fear is invoked by the fact that four of them, the later ones chronologically, display hinted human and animal faces. At this stage, there is no visual damage, but if the tendency continues to evolve, Givati might start opting for literary themes over the painterly values he has been creating. Givati’s power lies in the abstract, which best displays his qualities despite the difficulties which it causes the viewer (Haaretz, 6 July 1984 [Hebrew]).

Yehudit and Shifra Givati, Tel Aviv, 1985

In contrast, Rachel Engel, in her article “Figures Returning to the Canvas,” prefers the new paintings:

There is a rather clear division between the two parts of this exhibition. The ‘old’ part painted some two years ago, and the other part, the new paintings, created in recent months. The latter display a great improvement and are marked by conspicuous awakening. Unlike the abstract of the past, the ‘present’ in Givati’s work is inclined toward the figurative, and as opposed to the somewhat opaque, somewhat faded coloration, it shifts toward sharper, more contrastive coloration.

Quasi-figures, human characters or animals, or a mixture of the two, dominate Givati’s new compositions. Behold: an ostensibly very large red head at the heart of a blue painting, a one-eyed head. And in the adjacent painting – two figures, possibly two heads, one – human, the other – a horse or a donkey. The artist paints with big, broad gestures, with heavy, saturated, momentous color strokes. He uses lush, dark, subdued, indefinite blues; shades of brown and red and green (Ma’ariv, 6 July 1984 [Hebrew]).

Gil Goldfine too, in his article “One of a Kind,” introduced a clear-cut division between reticent abstractions and bellicose expressionist canvases. His preference is clearly stated:

Givati’s monsters, drawn with tendrils, nostrils and broad beamed anatomical appendages, echo contemporary new paintings. They show a determination to enter the foray of that style with a bang. ... This does not occur in two horizontal abstractions painted before the more expressionist fare. They are beautifully brushed and planned. Givati plays with veiled transparencies and opaque densities, pitting one against the other with sensitivity and a knowledge of exactly what to do. … In the most rewarding picture in the exhibit, Givati harnesses a central ‘X’ configuration with stripes and open horizons in a perfectly balanced and delicately constructed composition that borders on a dynamic grid. His use of a warm grey with a mellowed rusty violet (akin to Kupferman) supports the composition, as if the glove was sewn to perfectly fit the hand. Here is one occasion when a painter has assembled form, shape, color and texture into one superlative painting (Ma’ariv, 6 July 1984 [Hebrew]).

Another view, an outright rejection of the change that led to the new works, was presented by Raffi Lavie in his review “Half Baked”:

Searches. Kitchen exhibition. Moshe Givati has undergone numerous incarnations in the past 25 years, from the lyrical abstract of the late 1950s, through figurative painting with influences of Pop Art, and back to abstract with fine nuances (as he recently exhibited at Sarah Levi Gallery). Apparently he has now become tired of applying one green on another green, and of the interplays of transparent and opaque. He now tries to introduce a more narrative statement. The result: hinted figures in his recent works. The problem is that these hints have not yet come to full fruition. Ultimately the color strokes and hues remain the main speaker. The change of composition by inverting the place of two attached paintings, does not solve the problem. To my mind, the works should not have been exhibited; rather, he should have continued to struggle with his thematic material and shown the public a more finished result (Ha’Ir, 6 July 1984 [Hebrew]).

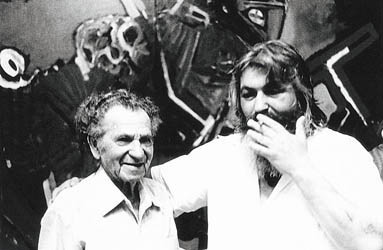

Moshe Givati and Pinchas Abramovich at the opening of Givati’s

exhibition on Ben Gurion Blvd., Tel Aviv, 1985

When Ruti Rubin (Direktor) met Givati and Intrator, they were under the impression that an ultimate encounter had occurred, a summit meeting that would lead to the big break – of artist and gallery alike. She wrote:

There was some fuse that awaited the right circumstances for many years, the right moment and the right people, for the flint to be rubbed, igniting it. Those who know the old Givati will not believe it when they see today’s monumental canvases at Dvir Gallery. The friction occurred, Givati was ignited (Hadashot, 29 June 1984 [Hebrew]).

But the fire was short-lived, and reality soon slapped the new partnership in the face. Givati is not the type of artist who adapts himself to given aspirations – however good they are. He is a born rebel. The attempt to “shape” him and influence his work did not yield the expected results. Such collaborations were not Givati’s forte, and his reservations soon showed.

The rift did not occur at once. In view of the great success, another exhibition was scheduled for the next year, and thus Givati achieved the heart’s desire of any artist: a show scheduled in advance. But the occurrences of the following year frustrated the hopes that accompanied the new path.

56 Ben-Gurion Blvd. – Home Exhibition: 1985

The “love affair” between Givati and Dvir was relatively short-lived. In December 1984 the exhibition “New Works,” featuring Jacques Greenberg, Yaacov Mishori, David Reeb, and Moshe Givati, was staged at Dvir Gallery. Raffi Lavie wrote succinctly that in this exhibition “Givati presents a beautiful work. Non-beautifying: a red sphere within a square set within a rectangle." (Ha’Ir, 7 December 1984 [Hebrew]).

The next solo exhibition planned for Givati at Dvir Gallery never materialized. For unclear reasons, Intrator suggested moving the exhibition to the Kibbutz Art Gallery. Givati was offended, maintaining that he didn’t need to have exhibitions “fixed up” for him. “I called Pichhadze and we organized my private apartment on Ben Gurion Blvd. I moved the family out and turned the place into a gallery,” he recounts in an extensive interview for Michal Kapra held in the home-turned-gallery. In the interview Kapra mentions that Intrator refused to exhibit Givati’s exhibition, a refusal later to be mentioned elsewhere as well, eliciting speculations as to the reasons. In the interview Givati told Kapra that he invested thousands of dollars in the home exhibition project:

It is all loans. He doesn’t have a penny in his pocket, which didn’t stop him from inviting a small band for the opening night and organizing a hafla at the Bikta for the guys. His second wife, Roni, many years his younger, and his two little daughters, Yehudit and Shifra, were evacuated from the apartment. Givati celebrates (Ma’ariv, 21 June 1985 [Hebrew]).

Givati had difficulties talking about his paintings. He wanted to go to Jacques Greenberg in Bat Yam, to hear the latter discuss his art. Having lost their way in the city, they finally find Jacques. The three sit somewhere, order beer, and Jacques explains Givati’s painting.

Givati sent invitations for the exhibition, and on the back mentioned that Dvir Gallery avoided presenting his new works. Raffi Lavie repeated this fact at the very beginning of his review:

Givati, who could not find a gallery to present his works, mounted an exhibition at home. A real gallery. Open daily from 17:00 to 20:00. (Ha’Ir, 31 May 1985 [Hebrew]).

Moshe Givati and Yosef Mundi at the opening of Givati’s exhibition

on Ben Gurion Blvd., Tel Aviv, 1985

Imanuel Bar-Kadma added:

Moshe Givati sums up an interesting experiment of breaking free from dependence on a gallery. His apartment on the third floor of an apartment building on Ben Gurion Blvd., was opened to the public like any real gallery… The effect is not one of a home, but of a gallery. Professional hanging, apt lighting, an atmosphere of pure art. Givati, an excellent painter of color who has returned from abstract to myth, will not let the galleries make a profit on his back – but holding such an exhibition has its price as well (Yedioth Ahronoth, 16 April 1985 [Hebrew]).

And Givati was willing to pay the price. In the interview with Kapra he names the sum he invested and explains that the entire investment was worth it, if only to realize that he had friends – the same friends without whose support he couldn’t have mounted the exhibition. He further notes that it was the most important exhibition he had ever staged for himself.

Dorit Kedar wrote about Intrator’s refusal to present Givati’s new works at Dvir Gallery:

I can rather sympathize with Dvir. Several weeks ago the gallery hosted a political Israeli-Palestinian exhibition whose painterly quality was beneath criticism. The owner must have been burned by the criticism and was reluctant to exhibit Givati’s problematic works (Al Hamishmar, 12 June 1985 [Hebrew]).

Kedar thought that there was something simplistic in the political contents Givati introduced into his new works. At the same time, she found the artistic result highly deserving, and the act of painting – strikingly powerful.

Ilan Nachshon too, in his article “The Rhinoceros and the Jellyfish,” referred to the titles of the paintings and the themes underlying the exhibition as a whole:

Sara Levi, Roni and Moshe Givati at the opening of Givati’s

exhibition on Ben Gurion Blvd., Tel Aviv, 1985

Moshe Givati, an essentially abstract painter, is pursuing the figurative and the symbolic with great emotional storms these days. His immense canvases are populated by pressing current affairs that call for definitions such as responsive painting, engaged art, or political art. The titles of the paintings call to mind posters in a demonstration on the city’s main square. He opposes Arik Sharon whom he depicted as a rhinoceros and a jellyfish; he is for ‘My Palestinian Brother’; against the orthodox (the affair of Teresa Angelowitz’s burial); and has decisive opinions in the stowaway affair (incidentally, the latter two are, to my mind, the best paintings in the exhibition). Add to all this themes such as The Binding of Isaac, a Masochistic Grandfather, and Teeth Pullers, and you can guess at the explosiveness of his easel this time.

There is a big gap between the blatant, violent titles and his artistic skill. I would not have lingered on them, if he hadn’t been dragged after them in his paintings. The verbal statement occasionally takes over the canvas, flattening it unnecessarily, mainly when Givati turns to the symbol, Jacques Greenberg style. On the other hand, when he emphasizes practice, his power as a painter is revealed.

The seasoned Givati has a proficient hand and a variegated colorist capacity, in red, purple, blue, and white. His canvases are masterfully constructed. His expressive brush strokes consist of free stains with multiple sensitivities, of contours that create division and balance, and occasionally of figures and symbols. They convey feelings of anxiety, threat, and distress. I prefer his hinted version which maps out a mental state in place and time, over the harsh, overt declaration (Yedioth Ahronoth, 7 June 1985 [Hebrew]).

Raffi Lavie, who as aforesaid referred to the exhibition space as a real gallery, never mentioned Givati’s titles in his article (“Too Much Purple”). He aimed his criticism directly at the body of the canvas – at the pure painterly problems:

The three large works, which are the core of the exhibition, possess great power articulated by large lumps of color confronted with linear brush strokes. Hints of heavy, raw figures, and the coloration, which comprises mainly pressing earth colors, reinforce this. The excessive use of purple slightly softens the coloration, rendering it less personal.

The group of heads created with soft texture and small, variegated strokes, appears like the work of another painter. Like a blown miniature that gives a near-surrealistic impression. These works are more ‘beautiful,’ riper than the large ones, but also more anemic. They could have possibly been more impressive had they not been hung side by side (Ha’Ir, 31 May 1985 [Hebrew]).

Heads: 1985

Givati’s “heads” in this exhibition were not the first in his oeuvre. Other heads emerged prior to this exhibition, in other connotations and times, and were yet to emerge on occasion in his future works as well. Givati, however, never conceived of an annotative code for deciphering the hidden meanings of the recurring image in his works. It is oriented neither to formalist interpretation nor to symbolic interpretation. Givati has always painted from the gut, but without abandoning the critical gaze. Even if it is possible to offer literal interpretations to his painterly language, in any event his signs shed all symbolical and thematic footholds, transforming any interpretation into an abstract compositional element.

While formally the “head” emerging in many of Givati’s works interrupts the total abstraction of his canvases, the interpretation required to read the secrets of this figurative element remains within the realm of abstract, perhaps within the realm of the psyche, which is, in any case, within the field of the study of abstract, the field of the unconscious.

The heads emerging by themselves are usually dissociated from a body, dominating the entire canvas. These are horrifying heads that emit their entire content outward. Each head has its own color, texture, expression. Some are more beastly, others almost human. Among them there are aliens, blind, open-mouthed, robot-like, suggested, alienated, frightened, deconstructed, blurred, psychedelic, red, green, pinkish, shrouded in black, green, illusive, crazed blue. These are heads that have been drawn from the vapors of alcohol and hallucinatory drugs; together they form a psychic map of a single self-portrait.

Ten large-scale canvases presented in the exhibition at Ben Gurion Blvd. were photographed for folio-size posters. Ronnie Dissentshik printed them at the Ma’ariv press. In September of that year Givati exhibited his monumental paintings in the basement floor of Dizengoff Center in order to promote the posters.

Studio Givati: 1987

In 1987 the Givati family was forced to move from the spacious apartment on Ben Gurion Blvd. into a smaller apartment, and Moshe Givati entered an alcohol rehabilitation program in a center in Ramat Gan. Concurrently, he became involved in a quarrel with the Artists’ Association board, and quit his teaching position at the Artists House on Alharizi Street. The new apartment was too small to contain his “painters’ shop,” and for the first time in his life Givati separated his living place from his work space. He rented a shoe warehouse on the fourth floor of a building on Neve Sha’anan Street in the city’s south. With a big hammer he demolished the walls that separated the two rooms, thus creating one big space. His faithful students from the Artists’ House followed him to Neve Sha’anan, and in addition he advertised in the papers, trying to draw students to “Studio Givati for Painting” near the Central Bus Station. He liked the group of students that gathered around him, and taught them in his unique way. He gave each of them a key to the studio, and they were invited to enter at any time and do as they pleased.

In April of that year Givati staged an exhibition at the Artists’ House, comprised mainly of monumental canvases he had painted in the two previous years. Following that exhibition, critic Nissim Mevorach maintained in his article “A Struggle against Grayness” that these monumental canvases manifest the attempt to break free from the coloration typical of the “Avni Institute” school which considered gray to be the richest of colors. Mevorach was highly impressed by the abstract canvases in which hinted natural forms, human profiles and silhouettes of evil beasts were interspersed, but noted that smaller formats would have been more befitting (Haaretz, 24 April 1987 [Hebrew]).

Dorit Kedar in her review “The Taste of Cool Candy” described Givati’s brush as “powerful, expressive, hurting, pressing.” At the same time, she regarded the large canvases as an obstacle:

The most convincing painting, which indisputably deserves to be presented in any respectable museum in the country, is a relatively small work addressing the figure of the model Laila. Laila easily merges with the abstraction around, she is not alienated to the empty space next to her, and the rather monochromatic color scale does not make her less expressive. Another good painting is the most radical one, alluding to the abstract form of a skull (Al Hamishmar, 17 April 1987 [Hebrew]).

Raffi Lavie reviewed the exhibition in his article “Plenty of Room,” where he commended “one beautiful painting a la Van de Velde, and next to it, another painting which is interesting without reminding anyone else.” About the rest of the paintings he wrote that in previous exhibitions Givati presented more serious works (Ha’Ir, 3 April 1987 [Hebrew]). After the opening at the Artists’ House Givati went to drink at the Red Bar in north Dizengoff with friends, among them Avigdor Stematsky, Dvora Schocken, Ami Levi, and others.

Laila Schwartz modeled in those days at the Artists’ House. When Givati needed a model, he used to invite her to his studio at the Central Bus Station, where she also participated in a documentary film created by Honi Hameagel about Givati, with the participation of Jacques Greenberg and Nir Hod, who worked as Givati’s assistant for a while.

Nir caught me one day at the Artists’ Association and asked whether I needed an assistant. I said why not, and he followed me to the studio on his motorscooter. He worked with me for several months and was very diligent. He worked from eight in the morning until noon, and then went to school. We had an agreement, that he doesn’t bother me when he has nothing to do. I showed him the wall he could use, the papers and paints, and told him that he could paint when he had nothing to do. I remember that his handwriting was entirely illegible. He used to come over from the Thelma Yellin High School of the Arts and stretch canvases. He ran errands like a devil of a fellow, he was truly fantastic. He once invited me to a party with his father. I came with Jacques Greenberg. His father pulled out some quality vodka and we had a great time.

When the exhibition at the Artists’ House closed, Givati cut all the monumental canvases he exhibited there into smaller canvases. He was in economic distress and recycled canvases so he could continue working. His money shortage did not keep him from buying materials which he freely gave out to his students.

The studio was regularly attended by Yael and Gigi, Gili and Tsahi, Ruta and Tamar, Tal, Yuval, and Yifat. Gili, who had a cockroach phobia, discovered a large painting by Givati starring a giant cockroach one day. Surprisingly, he asked for the painting which he hung in his room. Three of Givati’s students were later admitted to the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design, Jerusalem. When they identified their teacher, the puzzled Bezalel lecturers said this was nowhere to be seen in their works. Givati regarded this as a compliment.

The students used to come and go, and come again. In the studio they always found an open ear, a place to work, and unlimited painting materials. Givati remembers them fondly. That same year, one of them, Tsahi Reich, published a profile in Ma’ariv which briefly summed up Givati’s life, focusing, inter alia, on the studio near the Central Bus Station:

Givati, a man with doubts, with anxieties, requires extensive recognition from his surroundings, very long periods of adaptation to unknown places. Today, in his new studio, ‘Studio Givati,’ on Neve Sha’anan Street near Tel Aviv’s Central Bus Station, he sits and waits. Listens to the radio, passing occasional criticism on the radio people in the country who talk too much, eats yogurt and fruit he brought in a bag which Roni, his wife, prepared for him, and drinks beer he bought in the kiosk downstairs. But he doesn’t paint. Not yet. He is busy getting used to this place which up until two-three months ago served as a storeroom for one of the shoe stores downstairs on Neve Sha’anan Street, where most of the bus drivers and Egged members buy shoes for themselves and their families.

On a chest of drawers in the corner lies a small pastel painting depicting Givati, created by Yifat, one of his students at the studio. Under the graying beard in the portrait appears an inscription: ‘Moshe Givati is a big man; a hundred kg. at least.’ Even Givati, who admits that he cannot maintain close relationships, cannot deny that human warmth, some kind of love, is flowing here. Givati looks after his students. They feel it. They let him feel that they feel it: ‘What I have today, for better or for worse, is the studio,’ he says. ‘I make sure that a person who has just started painting, will have the physical conditions of a professional painter, and that someone who has a strong desire to paint, will be able to realize it, the way a professional painter works, that he will be able to work as well.’ It is not an ideology. There is no compassion here for the incapable. ‘It is the elementary decency required of a human being, who takes upon himself the privilege of instructing someone else, and I say instructing intentionally. I will not tell a person: paint an apple for two years, and then we’ll talk.’

Givati is the most beloved hated person. He has already managed to quarrel with all his friends, to insult them, to speak rudely more than once to too many people, even those who wanted to help him…

Givati’s recent exhibition, which included paintings from ‘86-’87, focused on the theme of Indians. It was exhibited at the Tel Aviv Artists’ House. The title ‘Indians’ was not published. ‘For some reason, the Artists’ Association decided that it was a nonpolitical body,’ Givati tells me, ‘so nonpolitical that someone thought that the word ‘Indian’ was a codeword for Palestinians, so I was not allowed to publicize the title of the exhibition’…

In preparation for the article Reich went to talk with Givati’s friends, actor Asher Sarfati and playwright Joseph Mundi. They had only good things to say about Givati, and expressed their appreciation for him, for his insistence in clinging to his path despite the difficulties raised by the establishment and the harsh struggle for existence:

For the six years since his return to Israel, much ink has already been spilled on him. Givati is what they call ‘good journalistic material.’ They wrote about the alcohol, the nicotine, the madness, the savage, the tormented artist, the impulsivity, whatnot, the self-destructiveness, curses, rudeness, about all the crap that he does when he gets drunk, how he cut himself with a fork, how he mooned Oded Kotler’s dumbfounded face, about anything that might make a headline. They somewhat forgot that he is an artist. Givati is a little angry, but accepts this… In the end, Givati does not equal the number of beer bottles lying daily on his desk, or the size of the scar on his right arm. Givati is, in fact, his paintings. ‘Painting is all I have,’ he says. ‘In my painting there is a lot of the neurosis within me. I paint what I paint. And it is me. My painting is me, for better and for worse.’…(Ma’ariv, 14 August 1987 [Hebrew]).

The Late 1980s

Givati tried to drop the alcohol, but managed to pull through only for short periods, and each time went back to drinking. His personality and the combination of alcohol and drug consumption started to take their toll on both his personal life and his art. In 1989 he divorced his second wife, Roni, who moved with his daughters to Moshav Tsohar in the Negev where he used to visit them on the weekends.

All these mental tribulations were perpetuated on the giant canvases which Givati stretched tirelessly in the studio. His works were filled with violent motifs which expressed great anxiety and horror. He was subjected to mood swings and fits of anger, and was controlled by strong emotions. He used to paint impulsively, then erase and paint again, and so on and so forth. When he was sober, the anxieties and doubts would infiltrate deeper. As far as the affinities of art to alcohol and drugs go, Givati’s personality is clearly congruent with documented behavioral patterns exhibited by other artists, among them writers and poets, with similar inclinations.

Between this chapter and the next, Givati returned to another period of abstract painting, where suggested images burst out in a blur, semi-defined and semi-obscure. Ami Steinitz, who taught at the Kalisher School of Art, saw these paintings and organized an exhibition for Givati in the school’s Gallery. Ami Levi loaded the canvases into his car and took them to the gallery. Together with Givati he mounted the loose canvases, which were not stretched on frames, but rather nailed directly to the wall. Next to these canvases they mounted another work which consisted of four plywood panels attached one to another, where color was not faded but rather shiny and flatter. In the evening, Steinitz came to the gallery and adjusted the lighting. There was no official opening and no invitations were sent. Following the recommendation of Kupferman, who happened to pass by, one of the paintings was purchased for the Phoenix Collection.

Ruti Rubin Direktor wrote about the exhibition in her review “Lighter than Pale”:

In recent years Givati emerges once every year or two with a new exhibition, each time in a different gallery, each time with a different story. Not that there are stories, on the contrary: the stories gradually disappear (from the canvas, not from his life), giving way to a less and less identifiable world. In retrospect, Givati has given up not only the images, but also the vivid coloration, and constructed for himself a more obscure, paler palette.

Based on the new works in Kalisher, one can almost dare assume that Givati’s life has also reached a slightly more stable station, at least for the time being. Why one requires psychologisms at all vis-à-vis Givati’s works, this is another question, but it is a fact that they come up. His large canvases convey a dull sense of surrealism, not the type that can be ascribed specifically, but only in terms of the projection of strange images that ostensibly emerge from some surreal subconscious. The images are irritating in their inability to become elucidated, if only for a split second, and allow one to touch them. One minute they recall certain things, giving the impression that they will soon clarify their real intention – but forthwith they turn vague again and become straight lines, semi-circles, and other indefinite things again…

The canvases themselves – some are not even stretched on a frame but rather nailed to the wall. The canvas is raw and crude, without priming. The color is absorbed in it, acquiring its coarse materiality, and most of the colors appear as though they were washed with a lot of white or gray, at times to the point of calcification… General obscurity emerges as the main feeling in Givati’s paintings…

Givati’s vagueness is, in fact, painted very accurately. With great confidence he drags his brush across the entire canvas, once again proving that throughout all his tribulations, he has remained a good painter (Hadashot, 12 March 1989 [Hebrew]).

But, as aforesaid, the abstract episode was only an interlude before the figurative dimension once again took over Givati’s canvases, this time in full force. The transitions from one group of works to another were often characterized by radical differences of approach, which were not calculated in advance, but rather surfaced from the subconscious. In her review, Rubin Direktor concluded from the atmosphere that prevailed in the light-colored canvases that “Givati’s life has also reached a slightly more stable station.” But stability was far from Givati, and his tempestuous life couldn’t have been farther from the tranquil paleness of his colorful palette. Several days after Aviva Uri’s passing, Ariella Azoulay, who set out to check the state of the artists in the city, came to visit the figure who had fuelled the city’s gossip columns. She published her impressions under the title “Portrait of the Artist as a Wretched Man.” Azoulay opened her article with a description of the man revealed to her after climbing to the fourth floor where his loft was located:

Let’s play a game of associations. What does the word painter tell you? Long hair, faded jeans, tormented gaze, damp attic, empty fridge. A meeting with painter Moshe Givati in his apartment brings these images back to life. A dark staircase in an old building at the heart of the Central Bus Station, leads to the attic that serves Givati as a studio and a home. He paints, eats and sleeps in a huge space furnished mainly with monumental paintings, in various stages of work, leaning against the walls. Givati, sitting down in gray sweats and long hair, surrounded by countless beer bottles, completes the picture. Givati says that he is one of a rare kind of artist not bothered by the livelihood difficulties and the lack of establishment support. ‘My struggle for existence is an integral part of my art. I wouldn’t want to be dependent on any political or municipal body. I am an entirely free man, by choice. Painting is my mania, and as a mentally ill person I cannot demand anything from the authorities. Being an artist is my privilege, God’s gift, and just as a religious man reports every morning to pray to his Creator – fearlessly, thus the artist wakes up every morning for his art prayer, and must not expect anything in return (Haaretz, 5 November 1993 [Hebrew]).

The Neve Sha’anan Studio days were replete with permutations. The place was always full of people – students, models whom Givati invited on occasion for specific needs, gallery owners, art dealers and collectors who arrived from time to time to view or purchase paintings, as well as friends and acquaintances who passed by and went in to have a drink, smoke something, hang out. Collectors brought each other over, and contact with them enabled Givati to live off his art:

My lawyer brought over architect Charles Dorell who built villas for the very well-to-do. He used to come to the studio and pick large-scale works for the houses he designed. He left the pay arrangements to me, and I always had difficulties with this. Sometimes I felt like a merchant in a cattle market. I lived off painting, but it was not always easy to let certain situations go without a response. One day some fashion designer from Rome was brought to me. He commissioned a large-scale painting for his living room. Following the short meeting I had with this delicate looking Italian man, the figures of the young people from the film Death in Venice came to my mind. I called Laila Schwartz and told her that I was looking for models. I described the specific qualities I needed, and she sent Michal who studied art at Kalisher.

Michal was the major model in the painting later called Cinderella. She was tomboyish and fitted the fantasy I wanted to realize on canvas. Several months later the Italian came back with his sister, who was a severe looking Catholic. They looked at the painting, turned pale and left the loft empty-handed. The painting remained in the studio and was later purchased by a businessman from Belgium. I don’t even have a photograph of it.

While Cinderella was a commissioned painting, it became the first link in the series “Children of Paradise” – a group of large-scale works painted within a short, intense time span filled with thrills in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The series as a whole was inspired by Pinhas Sadeh’s novel Life as a Parable which deeply influenced Givati at the time. From the monumental canvases burst forth a myriad of young figures that seemed to bring the set of figures from Sadeh’s novel back to life. They all seemed realistic yet somewhat magical: an atmosphere that stemmed from the quest for meaning and beauty, which spawned love, suffering, straying, and struggle. Through his identification with the novel’s point of view, Givati modeled a set of existential states that unfolded in an ongoing ritual of youth and freedom, under the threat of imminent destruction.

A., a young woman whom Givati met at Café Kassit and later in the pub across the street from Dvir Gallery, became his partner and moved into the loft. In this period Givati became fanatical about his privacy. The studio/home was visited mainly by models and collectors, who had to schedule their arrival in advance. Throughout the entire series Givati worked with models who moved about in the space where special lighting cast their moving silhouettes on the walls. In a quick brush drawing on the canvas he would freeze the silhouettes’ motion. This was a good, stormy period in his life, a type of a never-ending celebration, and the sense of euphoria that filled it is evident in the motifs emerging from the paintings in this series, including images of young men and women, unidentifiable animals, twined vegetation, and an atmosphere permeated with refined eroticism. Givati’s good friend, poet and stage artist Ficho (Itzhak Ben-Zur) used to visit the studio in those days and join the moving silhouettes alongside the models. His figure appears in at least two paintings in the series. Givati and Ficho maintained a long friendship. After his passing in 2005, Givati found a poem that Ficho had dedicated to him, which he inscribed on a portrait photograph of himself that he inserted into one of Givati’s sketchbooks.

|